Have you ever started a project and felt stuck because you didn’t know where to begin or how to get to your end goal?

For many learners, especially those who experience differences in planning, attention, or memory, even simple tasks can feel heavy. Task analysis helps by breaking larger tasks into smaller, manageable steps that are easier to teach, learn, and measure.

By clearly outlining each step, educators and families can reduce barriers and build independence, one step at a time.

In this article, we’ll explore the history of task analysis, its applications in schools, clinics, and homes, and practical steps for creating your own, along with strategies to track progress and support the unique needs of your learners.

Click here for the TL;DR summary.

What is Task Analysis?

Task analysis is a method of making tasks more accessible, by breaking them down into smaller, more manageable steps. In order to break tasks down, they are separated into component parts and the actions needed to complete it as expected.

This strategy makes instructions easier to follow. Long, multi-step tasks can be hard to finish for neurodivergent people to see through to completion accurately, due to difficulties with working memory, attentional control, and planning skills. These challenges can make it difficult to complete tasks accurately, often leading to procrastination or delayed task initiation.

Task Analysis and Executive Functioning

Executive functioning is the set of skills we use to plan, organize, start, finish, and self-monitor. Task analysis is a helpful tool that can be used to support the development of these executive functioning skills. Below are ways in which task analysis can support different executive functioning skills:

- Planning – Task analysis helps us break tasks into smaller, manageable steps that help learners understand the order of actions needed to reach their goal.

- Organization – Task analysis provides a clear structure for tasks, which helps learners keep their materials, information, and steps in the right sequence.

- Task Initiation – When a task is broken down into steps, it’s not as overwhelming or unclear. This makes it much easier to take the first step and see the task through to the end.

- Working Memory – Task analysis helps reduce the cognitive load of completing tasks by giving learners a concrete visual or written reference, without being expected to hold all that information in their mind at once.

- Self-Monitoring – Task analysis allows learners to check off completed steps, reflect on their personal progress, and identify areas where they need additional support. This helps learners visualize their performance and feel confident in their ability to reach their goals.

History of Task Analysis

Task analysis actually has its roots in the training of military personnel in the United States (p. 1). This procedure was originally used to help service members understand performance objectives and the specific responsibilities required to complete complex tasks.

In the 1950s and 1960s, this structured approach was quickly adapted for use in education (p. 1). School leaders and instructional designers began applying task analysis to plan the sequence of curriculum, making it easier to support learners in the classroom. This approach helped educators break down instructional objectives, identify the subtasks students needed to master before completing a larger task, plan instructional activities, and design performance-based assessments. Today, task analysis is used in various settings to help make operations run smoothly.

Types of Task Analysis

Next, we will explore the different types of task analysis and how each approach can help break down tasks to support learning and daily routines.

Hierarchical Task Analysis (HTA)

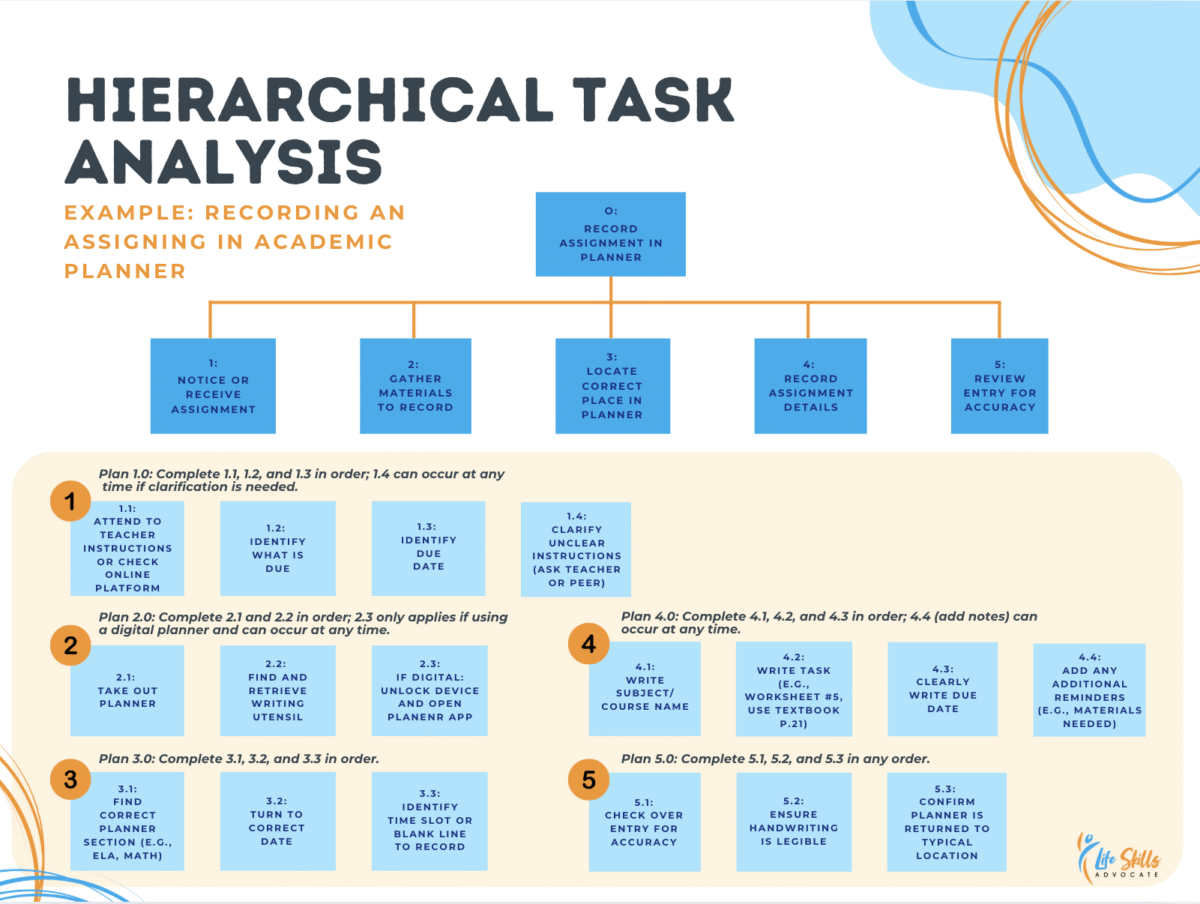

Hierarchical Task Analysis (HTA) is used to answer the question: How do you do this task step by step?

It breaks a task down into a main goal, followed by subgoals, and then operations and considerations. This creates a visual tree hierarchy, making it easier to see each action and the order in which it should be completed. HTA is especially helpful for teaching learners step-by-step routines, which can support executive functioning skills like planning, sequencing, and self-monitoring. Over time, learners may be able to break down tasks on their own or complete them automatically without needing the full sequence, but having the hierarchy available is still useful on days when focus or memory is limited.

Goal-Directed Task Analysis (GDTA)

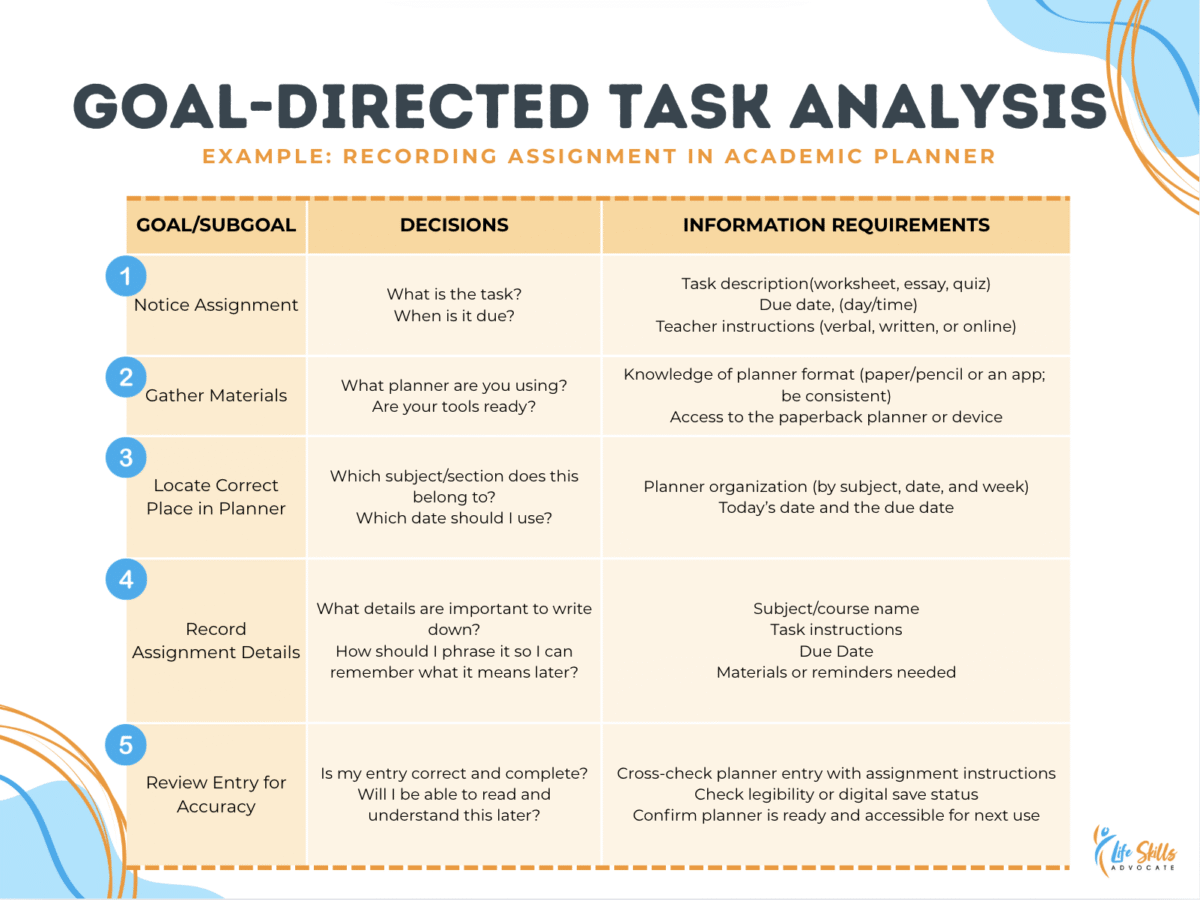

Goal-Directed Task Analysis (GDTA) answers the question: What is the learner trying to achieve in different contexts, and what information do they need to succeed?

GDTA focuses on understanding the specific goals a learner wants to accomplish and the information or resources they need to reach those goals. This approach focuses on key decisions the learner makes and the information they need at each point.

It assumes attention and problem-solving are limited, so surprises can lead to errors. Unexpected challenges or unanticipated steps can easily lead to errors and make it challenging to complete goals. GDTA helps anticipate these potential barriers using the following three elements:

- Breaking down the task from start to finish (e.g., tasks and subtasks)

- Identifying critical decisions (What? When? Where? How?)

- Clarifying what information is necessary to achieve the desired outcome – What do you already know about this process, and what do you need to learn in order to complete it?

Current Applications

Task analysis is used in many settings, including schools, clinics, and homes, to teach skills and support independence.

Schools

In schools, task analysis helps design instruction and support each learner’s needs. The hierarchical structure of task analysis makes it useful for identifying opportunities to embed scaffolding, or step-by-step support, within classroom lessons, daily routines, and social interactions. Educators can use task analysis to identify and anticipate potential barriers that may prevent learners from successfully completing a task or meeting classroom expectations. This can also help educators spot skill needs and plan supports through direct and repetitive instruction on the steps necessary to reach their end goals.

Task analysis can be used as a part of universal design for learning to help all students develop independence in various academic and daily living skills.Task analysis is often used in special education to focus on work specific to each learner and help develop the skills necessary to transition into settings after graduation.

Clinic Settings

Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) often uses task analysis to teach daily living skills. Many routines, like brushing teeth, bathing, dressing, cooking, and chores, include smaller steps that lead to one goal. Task analysis lets teams practice those steps, which can help people who benefit from concrete guidance. Many everyday tasks have subtasks that are not always taught directly. Using task analysis can reduce overload and support confidence during daily routines.

ABA often uses chaining to teach multi-step tasks. In chaining, the learner practices each step in order and moves to the next step after they perform the current step correctly. Independence is demonstrated when the learner can complete each step on their own and connect the steps into a routine. If you consider ABA, look for consent-based, goal-aligned practice. Ask how prompts are used and faded, how data are shared, and how the learner’s preferences guide day-to-day decisions with the support team.

Home

Task analysis can certainly be used in the home environment to help with daily living routines and self-care. If your learner receives clinical or school-based support using task analysis, it’s important to connect with your learner’s team to learn how you can use the same strategies at home. The more that your learner uses these skills in various settings, the more that they will generalize these steps across settings.

If you are not sure if your learner is explicitly taught these strategies, you can inquire about this in addition to other terms like “scaffolding,” “chaining,” or “chunking.” Many educators may not explicitly use the term “task analysis” but those same strategies are being taught and referred to in other ways.

Steps to Creating a Task Analysis

Soon, you’ll be able to implement task analysis when supporting your learners!

Below are the steps and considerations for setting up a task analysis, using the example of “recording an assignment in a planner.”

Step 1: Choose a Task to Teach

Start by identifying the main goal, or overall task, that the learner needs to complete.

In the examples above, we broke down the main task of “recording assignment in academic planner.”

Step 2: List the Steps Needed to Complete the Task

Write out the process from start to finish, making sure no steps are skipped. It will be helpful to walk through each step of completing the task on your own and write them down as you go. Your steps and substeps should be broken down enough that you could teach the process to someone who has never done the task before.

Example: Open planner → Find today’s date → Write subject → Write assignment specifics → Write due date

Step 3: Break the Task into Subtasks

Steps can often be split into smaller, more detailed parts. In the planner example above, each of the five steps could be turned into its own process if needed. How much you break it down depends on the learner. Some learners may only need a few clear steps, while others might struggle with specific parts and need extra detail. You usually find this out after trying the task analysis and seeing what works and what doesn’t.

It’s often helpful to start a task analysis with lots of detail. This gives you a clear picture of what the learner can already do on their own and what they still need help with. If a learner shows “mastery” by completing all the subtasks independently and no longer needs to check the task analysis, that’s a good sign you can remove those smaller steps. At that point, you can mark that the learner is now fully independent with that part of the skill.

For example, when teaching how to put on winter clothes, a learner might follow a visual schedule but still put snow pants on backwards or gloves on the wrong hands. In that case, you would revise the task analysis to include extra steps that teach how to check if clothing is on correctly.

Step 4: Identify Any Skills That Need to Be Incorporated Into the Process

While you’re creating a task analysis, note any motor, academic, or executive functioning skills involved. Any difficulties in these areas may influence additional subtasks or considerations you incorporate into the task analysis.

For example, a learner with hearing loss, visual impairment, or fine motor delays may need steps for using assistive technology or accommodations when recording an assignment in their planner.

Step 5: Review for Accuracy, Clarity, and Behavior That Can be Measured

Make sure the steps are specific and observable so you can track the learner’s progress over time.

Instead of just stopping at “Record assignment,” use measurable subtasks such as (1) Write subject/course name, (2) Write task details (e.g., worksheet name, textbook page number), (3) Clearly write due date, and (4) Add reminders (e.g., materials needed). This also makes it easier to track data that will inform the team on steps that may might often that contributes to difficulties understanding the planner entry later on.

Step 6: Implement and revise as needed

Teach and practice the steps, adjusting based on what the learner needs.

For example, if the learner is struggling to remember to check the board for the assignment details, add a sticky note reminder to “look up before writing” as a visual cue. You might also determine that a student needs explicit instruction in self-advocacy, such as how to ask peers for the assignment details. This will help them get the information they need in other ways from the environment.

Collecting Helpful Data Using the Task Analysis

For each instance of task analysis, you can progress monitor a student’s success with this tool by keeping a checklist of each step and substep of common routines at school, as it relates to academics, social skills, and daily living skills.

Create a Checklist

For each task analysis, create a checklist of steps and substeps for routines related to the main goal that you’re working on. This process will look the same, whether you’re working on academics, social skills, or daily living skills. As you work through the task analysis, make a check for each substep the learner completed on their own, and use a different color to mark when the learner needed support and how many reminders (or prompts) they needed to complete each subskill. This helps you see at a glance which steps the learner completes alone and which need support.

Two different options for collecting data include:

- Single-Opportunity Data–Data collection stops after the student makes their first mistake in the process. This shows how far the learner can get independently, before needing help.

- Multiple-Opportunity Data–Every step of the main goal is scored, whether that subskill was performed correctly or not. This will provide you and the team with detailed information on which specific skills require more support and which the learner is independent with.

Establish the Baseline

Before teaching a skill, collect baseline data on the learner’s performance. Have the learner try the task at least three times and record each result. If those attempts are similar, three trials are usually enough for a starting baseline.

Summarize the baseline with the median of the three scores, which reduces the effect of an unusually high or low trial. For example, if the scores are 20%, 50%, and 40%, the median is 40%. If the results vary widely (for example 20%, 50%, and 90%), add a few more trials until the baseline is stable.

Aim for a baseline that reflects typical performance so you can set a clear starting point and track progress accurately (task analysis in ABA).

Track Growth Over Time

After establishing a baseline, monitor the learner’s progress both with support (prompting, scaffolding) and without support. You may choose to focus on one skill area at a time or track growth across multiple areas of functioning. Be sure to review results with the learner’s Individualized Education Program (IEP) team to ensure the strategy aligns with learning and transition goals.

Additional Resources

The Life Skills Advocate Executive Functioning Assessment can be used alongside task analysis to gather data on a learner’s planning, organization, working memory, and self-monitoring skills. Educators and families can target specific subtasks within a task analysis by identifying which executive function areas are strengths and which need support.

The Executive Functioning IEP Goal Resource Hub is a great place to explore ideas for executive functioning goals that align with the 11 areas of executive functioning and consider needs across academic, social, emotional, and daily living skills. Goals from the bank can be adapted to fit each learner’s unique needs and then integrated into a task analysis for structured teaching. Using task analysis helps make abstract skills concrete, supports targeted instruction, and allows progress and independence to be monitored over time.

TL;DR – (Too Long; Didn’t Read)

Task analysis breaks a complex task into small, clear steps. It helps with planning, memory, attention, and organization by making the next action obvious.

Two common approaches

- Hierarchical Task Analysis: shows the step-by-step path to complete a task.

- Goal-Directed Task Analysis: maps the learner’s goals, key decisions, and the information they need.

Where it’s used

Schools, clinics, and homes to teach academics, self-care, and routines.

How to start

Pick a task, list the steps, break steps into substeps, note related skills or supports, make steps observable, then teach and adjust.

Track progress

Use a checklist. Try single-opportunity data (stop after the first error) or multiple-opportunity data (score every step). Aim for steady independence over time.

Further Reading

- Adams, Rogers, & Fisk (2013) – Skill components of task analysis

- Mastermind (2025) – Understanding the Concept of Task Analysis in ABA Therapy

- Pratt & Steward (2020) – Applied behavior analysis: The role of task analysis and chaining

- Shipley, Stephen, & Tawfik (2018) – Revisiting the historical roots of task analysis in instructional design

- Wang, Yu, Chen, & Xiao (2024) – Mission-oriented situation awareness information requirements of submariners: A goal directed task analysis

- Life Skills Advocate (2020) – Executive Functioning Skills 101: All About Organization

- Life Skills Advocate (2021) – Executive Functioning 101: All About Self-Monitoring

- Life Skills Advocate (2020) – Executive Functioning Skills 101: The Basics of Planning Skills

- Life Skills Advocate (2020) – Executive Functioning Skills 101: The Basics of Task Initiation

- Life Skills Advocate (2021) – Executive Functioning Skills 101: Working Memory

- Life Skills Advocate (2025) – Pinpoint Executive Function Strengths & Challenges in Minutes. Get Your FREE Assessment!

- Life Skills Advocate (2024) – Practicing Real-World Self-Advocacy: A Guide for Neurodivergent Individuals

- Life Skills Advocate (2025) – Welcome to The Executive Functioning IEP Goal Resource Hub