If college feels like too many moving parts, these executive function strategies will help you plan your week, start assignments, and finish with less overwhelm.

You open Canvas (or Blackboard, etc.), see a dozen tabs, and suddenly everything feels urgent and impossible.

You are not lazy.

This is what happens when college asks your brain to be the planner, the timekeeper, the starter motor, and the quality-control department, all at once.

In this guide, I’ll show you a simple, repeatable setup for four things college demands nonstop:

- Turning syllabi into a plan you can trust (jump to section)

- Running a weekly and daily routine that reduces decision load (jump to section)

- Starting and focusing when your brain refuses (jump to section)

- Recovering when you are already behind (jump to section)

I’ll also cover how campus support and accommodations usually work, so you are not guessing in a moment of stress.

TL;DR

Executive function strategies work best when they build a simple system you can repeat, even during chaotic weeks.

- Start with one primary calendar: pull every due date from every syllabus into one place.

- Add mini-deadlines for big assignments (topic, outline, draft, final) so “due in three weeks” becomes “work starts today.”

- Do a 20-minute weekly review: check deadlines, pick 3 priorities, schedule 2 work blocks, and move anything that slipped.

- If starting is the problem, shrink the first step to 2 minutes and use a short timer to get momentum.

- Use accountability when possible (study buddy, coworking, tutoring center) to make starts easier and distractions less sticky.

- Finish with a “submit” checklist so completed work actually turns into points.

- If you need formal support, contact your campus disability services office early. Many U.S. colleges provide accommodations under the ADA and Section 504.

Note: This article is educational only and not medical, mental health, or legal advice. For personalized guidance, talk with your campus disability services office and, when relevant, a qualified professional.

If You’re Already Behind: A 20-Minute Reset You Can Do Today

If you’re already behind, the goal is not to “catch up on everything” today. The goal is to stop the slide by choosing the next right moves and communicating early.

Real-life example: you log into your LMS and see three missing assignments, a quiz you forgot, and a paper due soon. Your brain wants to either do all of it at once or avoid all of it at once. This reset gives you a third option: a short plan you can act on.

- Pick the next 1–2 deadlines (48 hours). Circle what affects your grade soonest (quiz window, lab, discussion post).

- Make a “not pretty” list. Write down what is missing and what is next, using the assignment titles from the LMS.

- Triage into three buckets: “Do now,” “Ask for an adjustment,” and “Probably drop or skip.” If you work a lot of hours or commute, assume you have less time than you want and plan smaller.

- Send one short email today. Choose the class where points are bleeding fastest or where the instructor is strict about late work.

- Schedule one support move. Office hours, tutoring center, writing center, or a study buddy session. Put it on your calendar like it’s an appointment.

- Do a 10-minute starter sprint. Open the assignment, copy the prompt into a doc, and write three messy bullets. Momentum matters more than quality at this moment.

Quick email script (edit to fit your situation): “Hi Professor [Name], I’m behind on [assignment]. My plan is to submit [specific item] by [date]. Is that workable in your course, or should I prioritize a different piece first?”

Why Does Executive Function Feel Harder in College?

Executive function often feels harder in college because college removes a lot of built-in structure, and your brain has to supply the planning, starting, and follow-through.

Here’s the real-life version: you open your LMS, see a quiz window, two readings, a lab write-up, and a paper that is “due in three weeks.” Nothing is happening today, but everything is happening. That is a lot. When the plan is fuzzy, your brain usually defaults to urgency, avoidance, or both.

What counts as executive function in college life?

Executive function is the set of skills that helps you manage yourself over time. In college, that can look like:

- Remembering what’s due (working memory)

- Choosing what matters first (prioritizing)

- Getting started (task initiation)

- Staying with it (attention control)

- Noticing when you’re off track (self-monitoring)

- Shifting plans when something changes (cognitive flexibility)

- Handling the stress that comes with all of it (emotional regulation)

For a deeper look at executive function, our Executive Functioning 101 Resource Hub breaks it all down in plain language.

The independence gap: high school vs college structure

High school often provides frequent reminders, shorter deadlines, and adults who notice missing work quickly. College often runs on syllabi, long-range projects, and “come to office hours if you need help.” That shift is big, even for students who were strong academically in high school. I’ve watched many students go from “I did fine before” to “Why can’t I keep up now?” simply because the system changed.

Why this matters: when you name the problem as a skills-and-structure mismatch, you can stop trying to power through with willpower and instead build supports that make college tasks startable and finishable.

Key takeaways

- College demands more self-management because less structure is provided for you.

- Executive function challenges often show up as planning, starting, focusing, shifting, and finishing problems.

- A reliable external system (calendar, weekly review, simple routines) reduces overload on working memory.

- Needing more structure in college is common, including for students who did well in high school.

System 1: Turn Every Syllabus Into a Plan You Can Actually Use

The fastest way to reduce missed deadlines is to turn every syllabus into one master plan you can trust.

Here’s the college reality: each class is a mini-universe with its own rules, dates, and hidden “gotchas.” If those dates live in five places (syllabi PDFs, your LMS, random screenshots, your brain), they will disappear at the worst moment. This system puts everything in one place so you can stop re-solving the same problem every week.

The 45-minute syllabus download

Pick one time this week (even if it’s not a perfect time) and do a quick “deadline sweep” for each class.

- Open the syllabus and the LMS calendar (if your course uses one). You’re looking for due dates, quiz windows, exams, labs, and big projects.

- Write down every due date in plain language. Use the assignment names you’ll see in the LMS, like “Discussion 3” or “Lab 2 Write-Up.”

- Put every due date into one master calendar. Google Calendar, iCal, Outlook, or any calendar you actually check is fine.

- Add reminders that match your life. If you commute or work long shifts, set reminders earlier than you think you need.

- Choose one task list. Keep tasks in one place, and let the calendar hold dates.

Mini-deadlines for big assignments

Big assignments are where executive function challenges show up the loudest, because “due in three weeks” does not tell your brain what to do today. Mini-deadlines create a start line.

| Assignment | Final Due Date | Mini-deadlines To Add |

|---|---|---|

| Research paper | Sun, Oct 20 | Topic picked (Oct 6), sources found (Oct 9), outline done (Oct 11), rough draft (Oct 16) |

| Lab report | Thu, Sep 19 | Data organized (Sep 16), methods written (Sep 17), results drafted (Sep 18) |

| Group project | Mon, Nov 4 | First meeting scheduled (Oct 14), roles assigned (Oct 16), shared doc created (Oct 16), first draft slides (Oct 28) |

One calendar, one task list, fewer surprises

The goal is not perfection. The goal is one reliable system that keeps you out of “surprise deadline” mode. If you miss a mini-deadline, that is useful information, not a moral failing. You adjust it in your weekly review, then keep going.

Key takeaways

- Put every due date from every syllabus into one master calendar.

- Add 2–4 mini-deadlines for big assignments so work starts earlier.

- Use the exact LMS assignment titles to reduce confusion later.

- Pick one task list and one calendar to reduce lost tasks.

System 2: Weekly and Daily Routines That Reduce Decision Load

A simple weekly and daily routine makes college easier because it reduces the number of decisions you have to make when you are already tired.

Example: it’s Sunday night (or Monday morning, or “whenever you finally remember”), and you are trying to hold five classes in your head at once. Your brain starts bargaining: “I’ll just wing it this week.” That usually ends with surprise deadlines and late-night panic. A short routine is a kinder option.

The 20-minute weekly review

Do this once a week at a time you can actually repeat. If you work long shifts, do it right after you get your schedule. If you commute, do it in a quiet spot on campus before your first class.

- Look at the next 7 days in your calendar. Spot deadlines, exams, quiz windows, and meetings.

- Pick 3 priorities for the week. Not 12. Three.

- Schedule 2–4 work blocks. Put them on your calendar like appointments, even if they are only 30–60 minutes.

- Add one buffer block. This is where slipped tasks go, so your whole week does not collapse when life happens.

- Update your task list. Move tasks that slipped, delete tasks that no longer matter, and write the next action for anything big.

A daily “start line” routine

The daily goal is not to plan your whole life. The daily goal is to create a start line so your brain does not have to invent one.

- Open your calendar and choose one “first task.” Make it concrete, like “open the lab doc and write the first two headings.”

- Set a short timer. Ten minutes is enough to get moving, and short enough to feel safe.

- Make the environment match the task. If focus is hard, choose a quieter location, use headphones, or put your phone in another room for the first sprint.

- End with a clean handoff. Write one sentence: “Next time, I will ___.” This helps future-you restart.

If you are not sure which skill is tripping you up (planning, starting, working memory, or something else), a quick way to name the bottleneck is the free executive functioning assessment. Naming the pattern makes it easier to choose the right strategy instead of trying random tips.

System 3: How to Start and Focus When Your Brain Refuses

If starting work feels impossible, you do not need a bigger lecture. You need a smaller start and a plan that makes focus more likely.

Example: you have a 20-page reading and a discussion post due tonight. You know you should begin, but your brain keeps sliding to anything else. This is a common executive function bottleneck, especially for ADHD and autistic students, because “start the assignment” is too vague to be startable.

The 2-minute start

The goal is not to finish in two minutes. The goal is to cross the start line.

- Open the document or LMS page. Do not decide anything yet.

- Copy the prompt into a doc. Create space for a messy first pass.

- Write three ugly bullets. Any three. You are proving to your brain that motion is possible.

- Name the next step in one sentence. “Next I will find one quote,” or “Next I will answer question one.”

Quick Chris (the author) note: my own brain reacts to big, fuzzy tasks with “nope.” In coaching, I see the fastest progress when students stop waiting to feel ready and instead make the first step so small it is hard to argue with.

Timers that do not feel like a trap

Some students hate timers because timers feel like pressure. The fix is to use a timer as a starter sprint, not a prison sentence.

- Set a 10-minute timer. Your only job is to stay with the first tiny step until the timer ends.

- When the timer ends, choose: stop, take a 5-minute break, or do one more 10-minute sprint.

- Keep a “restart note.” Before you stop, write one line: “Next time I will ___.”

Body doubling: borrowing someone else’s momentum

If starting alone keeps failing, add another person to the environment. You do not need them to help you do the work. You need them to make it easier to begin and stay in the lane.

- Study buddy: sit near each other, agree on a start time, then work quietly.

- Coworking: library table, campus study room, or a virtual coworking call.

- Campus supports: tutoring center, writing center, or structured study sessions.

If you are a commuter or you work long hours, treat accountability like transportation. Schedule it when you are already on campus, so it does not require extra effort later.

A realistic reading plan

For heavy-reading classes, the trick is to stop treating reading like an all-or-nothing event. Use a smaller loop that creates something usable for class.

- Preview first (3 minutes): skim headings, bold terms, and the first and last paragraph.

- Set a target: “I’m finding the author’s main claim and two supporting points.”

- Read in short chunks: 5–10 pages, then write a 2–3 sentence summary in your own words.

- Turn reading into output: write one discussion-post bullet while the reading is still open.

If you want a student-friendly list of study and executive function skills, the University of Minnesota’s ADHD academic success skills guide is a helpful reference.

Key takeaways

- A two-minute start can break the “stuck” loop and create momentum.

- Short starter sprints work best when you are allowed to stop when the timer ends.

- Accountability supports like study buddies and coworking often make starting easier.

- For reading-heavy classes, preview, chunk, and produce a small written output while the material is open.

System 4: Finish, Submit, and Recover When You’re Behind

Finishing is an executive function skill, and college often grades the last 10 percent the hardest. A “finish and submit” routine protects your points and makes it easier to recover when a week goes sideways.

Example: you wrote most of the paper, but it is still not turned in. This happens a lot because “submit” has hidden steps (formatting, citations, file uploads, confirmation screens) that get missed when your brain is tired.

The “finish and submit” checklist

- Re-read the prompt and rubric. Confirm you answered the right question.

- Do a 10-minute cleanup pass. Fix the title, headings, and obvious typos. Stop there.

- Check citations and format. Make sure the basics match what the class expects.

- Save the file with a clear name. Example: “HIST201_Paper2_ChrisHanson.docx.”

- Upload and click the final submit button. Many LMS platforms require more than one click.

- Confirm submission. Look for a confirmation message, timestamp, or submitted status.

- Capture proof. Take a screenshot or save the confirmation page.

Backlog triage in 15 minutes

When you are behind, the goal is to stop guessing. Triage creates a short plan based on points and deadlines, not guilt.

- List what is missing. Use the exact assignment titles from your LMS.

- Mark what still earns credit. If the syllabus says “no late work,” highlight that item for a conversation.

- Choose one class to stabilize first. Pick the class with the closest deadlines or the biggest grade impact.

- Pick the smallest high-impact task. A discussion post or short quiz often stops the bleeding faster than a perfect paper.

What to say when you need an adjustment

Keep communication short and specific. Offer a plan instead of a long explanation.

Script: “Hi Professor [Name], I’m behind on [assignment]. I can submit [specific item] by [date]. Is that workable, or should I prioritize a different piece first?”

If you’re still unsure what is realistic, office hours or a quick meeting with an academic advisor can help you pick a plan that matches your actual time and energy.

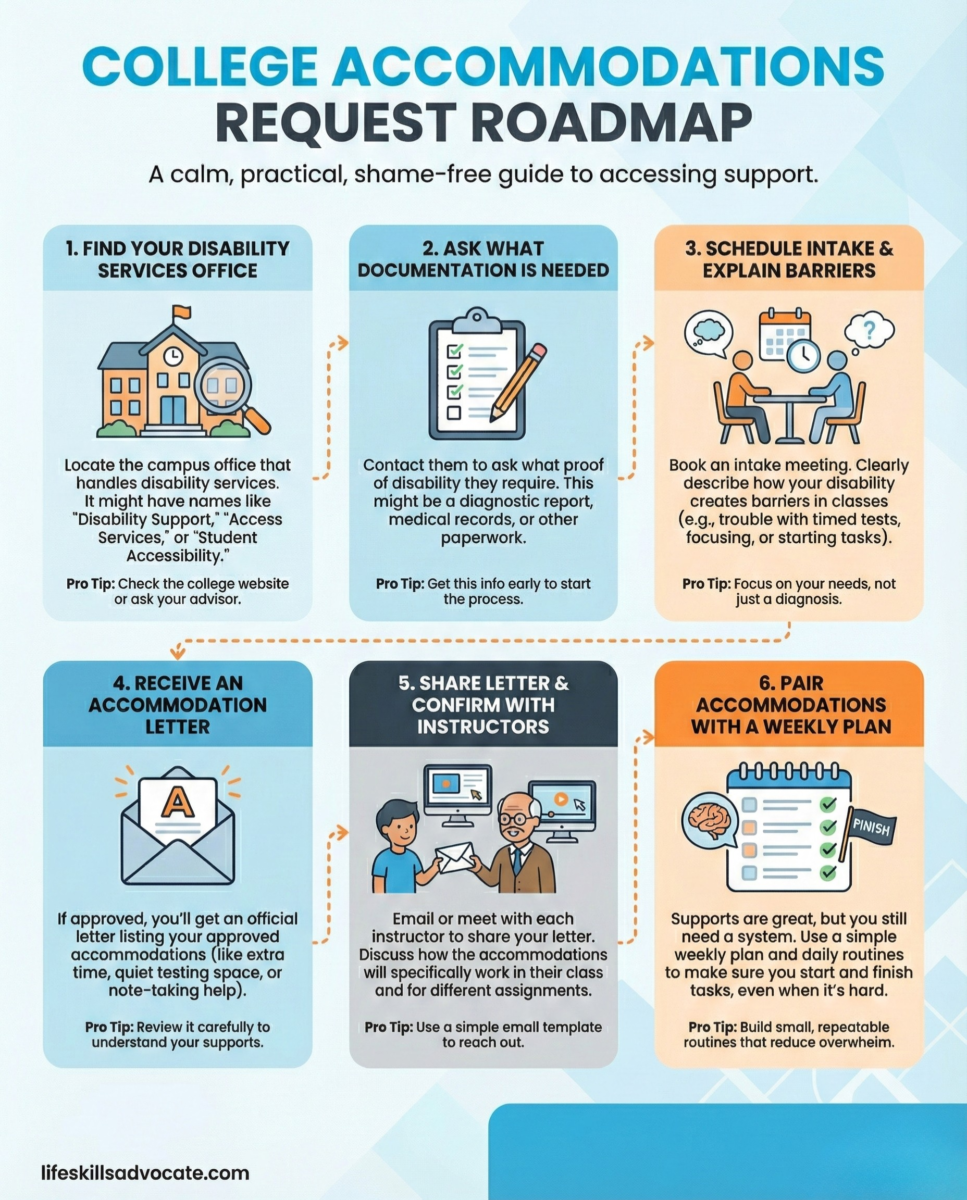

Support and Accommodations in College: What’s Protected and What To Do

If executive function challenges are creating access barriers in college, campus supports and formal accommodations can make school more doable, especially when they are paired with a simple plan you can actually follow.

Example: timed quizzes leave you frozen, you miss submission windows, or you cannot keep track of shifting deadlines across five classes. In moments like this, “try harder” is not a strategy. A support process gives you a clearer path forward.

ADA and Section 504 in plain language

In the U.S., most colleges are covered by Section 504 and/or the ADA, which means they must provide equal access for qualified students with disabilities. A helpful starting point is the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights guide Students with Disabilities Preparing for Postsecondary Education: Know Your Rights and Responsibilities and the U.S. Department of Education overview of Section 504 protections. For a plain-language overview focused on college, the ADA National Network fact sheet Postsecondary Institutions and Students With Disabilities is a clearer match than employment-focused ADA resources.

Quick expectations check: College accommodations are meant to provide equal access, not to lower academic standards. Schools can offer academic adjustments and auxiliary aids when needed for equal opportunity, but they generally don’t have to make changes that would fundamentally alter a program or create an undue burden, as described in Students with Disabilities Preparing for Postsecondary Education: Know Your Rights and Responsibilities and the ADA National Network guidance on college responsibilities.

One big shift from K-12: IEPs don’t carry over into college, and colleges don’t write IEPs. In college, students usually request accommodations through the disability services office and decide when to share accommodation letters with instructors. The student usually initiates the process through the disability services office and decides when and how to share accommodation letters with instructors.

What disability services typically needs from you

Every school has its own process, but the general pattern is: you contact disability services, ask what documentation they require, complete an intake, and discuss accommodations for your classes. If you want a clear overview of documentation expectations, AHEAD’s documentation guidance is a practical reference.

- Start early if you can. It is harder to set supports when grades are already sliding.

- Be specific about barriers. “I have ADHD” is less useful than “I miss quiz windows” or “I cannot finish timed exams even when I know the material.”

- Ask about timelines. Some offices need time to review paperwork and schedule intakes.

Common accommodations for executive function barriers

Accommodations vary by school and course, but students commonly ask about supports like extended time or reduced-distraction testing, note-taking supports, assistive technology, or registration supports that reduce schedule chaos. It can also help to ask for structure that supports follow-through, like clarifying interim deadlines or confirming submission expectations, so “more time” does not quietly turn into more avoidance.

Email templates: disability services and professors

To disability services: “Hi, I’m a student in [program]. I’m looking for support related to [barrier, like timed exams or task initiation]. What documentation do you need, and how do I schedule an intake?”

To a professor (after you have a letter): “Hi Professor [Name], I have an accommodation letter from disability services. What’s the best way to apply these accommodations in your course, especially for [exams, quizzes, labs]?”

When structured skill-building helps

Some students benefit from structured skills programs that teach planning, time management, and follow-through in a consistent way. For college students with ADHD, a multisite randomized trial of a CBT-based skills program reported improvements compared with usual services (multisite randomized trial of a CBT-based skills program for college ADHD). A DBT-based skills group has also been studied, but the published evidence includes a small pilot trial, so it’s best described as promising rather than settled (pilot randomized trial of DBT skills training for college students with ADHD). Skills programs are one option, and they usually work best when you also have a simple weekly plan you can repeat.

Key takeaways

- Many U.S. colleges provide accommodations under the ADA and Section 504 when a disability creates access barriers.

- In college, students usually initiate the process through disability services and share accommodation letters with instructors.

- Clear documentation and a specific description of barriers can make the process smoother.

- Accommodations can reduce barriers, and a simple weekly plan supports follow-through.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are executive functioning skills in college, in plain language?

Executive functioning skills are the “manage myself over time” skills that help you plan, start, focus, shift gears, and finish tasks. In college, executive function shows up in things like remembering deadlines, choosing what to do first, starting assignments without panic, staying on track during studying, and turning finished work into a submitted assignment. Executive function challenges are common, especially when college structure is lighter than high school structure.

Why can’t I start assignments even when I care a lot?

Task initiation is a common executive function bottleneck, including for many students with ADHD or autism, especially when a task feels big, vague, or high-stakes. Executive function is often described as the set of mental skills that support goal-directed behavior over time, including skills like working memory, inhibitory control, and cognitive flexibility (Cleveland Clinic overview of executive function). A practical fix is to shrink the first step until it is startable in about 2 minutes, then use a short timer to build momentum. If starting still keeps stalling, studying near another person or using a campus support space can reduce friction, even when you care a lot about the class.

How do I get through readings when my brain checks out?

A helpful reading strategy is to stop aiming for “perfect reading” and instead aim for “useful reading.” Preview headings first, pick a target (main claim plus two points), then read in short chunks and write a 2–3 sentence summary after each chunk. Turn reading into output right away by drafting one discussion-post bullet while the text is open. This approach reduces working memory load and makes reading feel less endless.

What’s the difference between accommodations in high school vs college?

In college, the student typically drives the process. Many colleges use disability services to coordinate accommodations under the ADA and Section 504, and students usually request support, share documentation, and provide accommodation letters to instructors. In high school, supports are often more built-in and staff may monitor missing work more closely. If you are used to adults catching problems early, college can feel like falling off a cliff, even with strong effort.

Are deadline extensions helpful for executive dysfunction?

Deadline extensions can help when executive function challenges create access barriers, but extra time works best with structure. Without interim deadlines, “more time” can quietly become “more time to avoid,” especially when stress is high. A practical compromise is to ask for an extension plus a short plan: a new due date, one checkpoint (outline or partial draft), and a quick check-in. The goal is access plus follow-through, not pressure.

Next Steps: Pick 2 Changes You Can Try This Week

If you try to change everything at once, your brain will probably vote “no.”

Pick two changes: one that improves planning, and one that improves starting.

- Planning pick: Do one 20-minute weekly review and schedule two work blocks for your highest-priority class.

- Starting pick: Use the 2-minute start plus a 10-minute timer for one assignment today, even if it feels messy.

If you are behind right now, do the 20-minute reset from earlier and send one short email today. A small, realistic plan beats a perfect plan you never start.

If you want structured practice (not just tips), the Real-Life Executive Functioning Workbook can help you work skill-by-skill with concrete exercises. If you want live support and accountability, executive function coaching for college students is an option. Coaching is educational support, not therapy or medical treatment.

If you’re a parent or supporter: Ask the student which two changes they chose, then offer one “body double” study session or one weekly check-in. Keep it short. Keep it practical.

Further Reading

- Executive Functioning 101 Hub (Life Skills Advocate overview of executive function skills)

- Free executive functioning assessment (Life Skills Advocate tool to identify skill bottlenecks)

- Real-Life Executive Functioning Workbook (Life Skills Advocate skill-by-skill practice resource)

- Executive function coaching for college students (Life Skills Advocate educational coaching support option)

- Section 504 protections (U.S. Department of Education overview)

- Postsecondary institutions and students with disabilities (ADA National Network overview for college accommodations)

- Documentation guidance from AHEAD (documentation and process reference for disability services)

- ADHD academic success skills guide (University of Minnesota student strategies and study supports)

- CBT skills program study for college ADHD (multisite randomized controlled trial)

- DBT skills training study for college students with ADHD (pilot randomized controlled trial)