If you are neurodivergent and everyday tasks suddenly feel heavier, louder, and harder than they used to, you might be experiencing neurodivergent burnout rather than a lack of motivation or discipline.

Neurodivergent burnout is a deep state of physical, emotional, and mental exhaustion that happens when your nervous system has been working overtime for too long. For many autistic and ADHD people, it can show up as losing skills you relied on, avoiding messages or calls, feeling overwhelmed by small decisions, or needing far more recovery time after work, school, or social events.

This guide is for neurodivergent adults and for the people who support them, including parents, partners, educators, and clinicians. Together, we will look at what neurodivergent burnout is, how it is different from more commonly described “work burnout,” the signs to watch for, and practical ways to reduce stress and rebuild capacity in daily life.

Understanding burnout in this way matters because it shifts the story from “I am failing” to “my brain and body are overloaded.” When you can see burnout as a nervous system and environment problem, not a character problem, it becomes easier to ask for support, adjust expectations, and protect your health, relationships, and independence over the long term.

TL;DR

Neurodivergent burnout is a deep kind of exhaustion that builds over time when your nervous system is overloaded by chronic stress, masking, and sensory overwhelm.

- Neurodivergent burnout goes beyond feeling tired and often includes chronic fatigue, brain fog, and a much lower tolerance for everyday tasks, people, and environments.

- Research on autistic burnout shows patterns of long-lasting exhaustion, loss of skills, and reduced independence that come from chronic life stress and mismatched expectations, not from a lack of effort.

- Many neurodivergent people notice more shutdowns or meltdowns, increased sensory sensitivity, and everyday tasks like cooking, showering, or answering messages suddenly feeling out of reach.

- Burnout can significantly affect executive function, so planning, organizing, remembering details, and making decisions all become harder, even if those skills felt manageable before.

- Recovery often requires both reducing demands and changing environments, for example unmasking where it feels safe, adjusting workloads, and creating more sensory-friendly spaces, rather than just taking a short break or vacation.

- Supportive options can include executive function coaching, workplace or school accommodations, and neurodiversity-affirming healthcare or mental health professionals, especially if symptoms are severe or long lasting.

This article is for educational purposes only and is not medical, legal, or mental health advice. If you are worried about your safety or someone else’s, please seek immediate support from a qualified professional or crisis service in your area.

What Is Neurodivergent Burnout?

Neurodivergent burnout is a state of deep exhaustion that builds over time when a neurodivergent person has to push through more stress, masking, and sensory overload than their nervous system can recover from.

How experts define burnout

In the medical and research world, burnout is usually described as something that happens at work. The World Health Organization definition of burnout focuses on chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed. It highlights three main parts: feeling exhausted, feeling distant or negative about work, and feeling less effective on the job.

This description is useful because it explains that burnout is more than being tired after a busy week. It is a long-lasting pattern that affects how you feel, how you think about your role, and how well you can function. At the same time, it has limits. It does not fully describe what happens when stress is not only at work, but also in school, at home, online, and in every social interaction, which is often the reality for neurodivergent people.

For neurodivergent readers, this matters because you might feel like you “should not” be burned out if your job looks reasonable on paper or if people around you say you are doing fine. The official definition does not always capture the extra load of constant sensory processing, social decoding, and masking.

How autistic burnout research expands the picture

Researchers and autistic adults have been describing something more specific than general work burnout. In autistic communities, the term “autistic burnout” is used for a state of chronic exhaustion, loss of skills, and reduced tolerance for everyday demands that can last for months or years. A qualitative study by Dora Raymaker and colleagues found that autistic adults described autistic burnout as a combination of extreme fatigue, fewer coping resources, and a sharp drop in independence after long periods of stress and masking.

Professional guidance on autistic burnout adds more detail. It notes that autistic burnout often follows times when demands greatly outweigh supports, such as major life changes, work or school overload, ongoing social pressure, or lack of understanding from others. People may report feeling “more autistic” than usual, with stronger sensory responses and less ability to cope. This can lead to more frequent meltdowns or shutdowns and a need for far more recovery time, as well as suddenly struggling with tasks that used to feel manageable.

Even though most formal research so far has focused on autistic adults, many ADHD and otherwise neurodivergent people recognize the same patterns. They describe long stretches of pushing themselves, trying to keep up with expectations, and then hitting a wall where even simple tasks feel out of reach.

A working definition of neurodivergent burnout

Putting these pieces together, we can describe neurodivergent burnout in plain language:

Neurodivergent burnout is a long-lasting state of physical, emotional, and mental exhaustion that happens when a neurodivergent person faces ongoing demands, masking, and sensory or social overload without enough rest, support, or accommodations. It often includes a noticeable loss of everyday skills, a lower tolerance for stress and sensory input, and a strong need to withdraw in order to recover.

Imagine an autistic or ADHD teacher working in a bright, noisy classroom with constant interruptions, paperwork, and staff meetings. For a while they manage by staying late, masking their distress, and using weekends to recover. Over time, they start waking up exhausted, forgetting simple steps in their lessons, crying during breaks, and finding it impossible to cook dinner or answer messages after work. That pattern is a classic picture of neurodivergent burnout, even if their job title has not changed.

Seeing burnout through this lens is important because it reframes the problem. Instead of asking “Why can I not just try harder?”, the better questions become “What demands are draining me?”, “Where am I masking or pushing past my limits?”, and “What needs to change in my environment and support system so my nervous system can recover?”

Why Neurodivergent Burnout Happens

Neurodivergent burnout does not come out of nowhere. It usually builds slowly when demands stay high, support stays low, and your nervous system never really gets to stand down.

Chronic stress and allostatic load

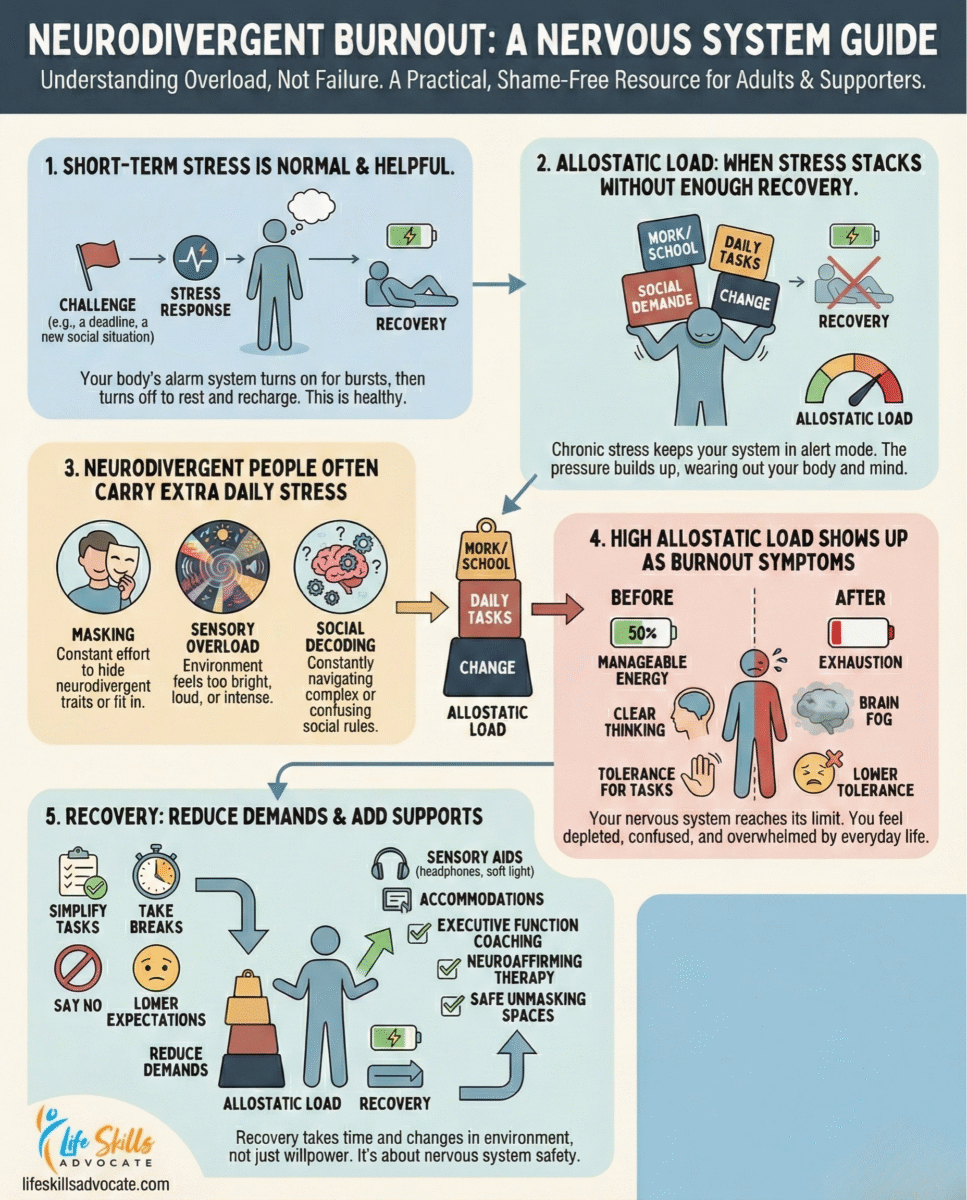

Our bodies are built to handle short bursts of stress. When something feels threatening, your brain signals your stress systems to turn on, your heart rate rises, and your body prepares to act. Once the situation passes, those systems are meant to turn back down.

Allostatic load is the term scientists use for what happens when this stress response is switched on too often or for too long. Instead of returning to a calm baseline, your body keeps operating in “alert” mode and slowly wears itself out. Over time, high allostatic load is linked to worse health outcomes and impaired thinking skills like memory, focus, and decision-making when stress becomes chronic.

For neurodivergent people, daily life often includes extra stress layers that many others do not see, such as constant sensory filtering, masking, decoding social rules, and recovering from misunderstandings. Even when nothing “big” is happening, your nervous system may be doing a lot of hidden work. That steady drain can raise allostatic load and make burnout more likely, even if your schedule looks normal from the outside.

Why this matters: When you understand burnout as the result of long-term pressure on your nervous system, it becomes easier to ask, “What can be lowered?” rather than “Why can I not handle this?”

Masking, camouflaging, and internal expectations

Masking and camouflaging are major reasons many neurodivergent people reach burnout. Masking means hiding or changing your natural expressions, interests, movements, or communication style to fit in or stay safe. Over time, that constant self-monitoring is mentally and physically exhausting.

Research on autistic adults shows that heavy social camouflaging is linked with higher stress and burnout, especially when people feel they must perform “being fine” at work, school, or in relationships to avoid judgment. Many ADHD and otherwise neurodivergent adults describe similar patterns, such as rehearsing every sentence before speaking, laughing off mistakes, or staying late to quietly redo work so nobody sees how hard it was.

Internal expectations add another layer. Messages like “I should be able to keep up if I just try harder” or “Everyone else is coping, so I must be the problem” push people to ignore early signs of burnout. That can delay rest and support until the crash is much deeper.

Imagine a late-diagnosed autistic or ADHD professional who performs confidence in meetings, laughs along with noisy team lunches, and stays after hours to catch up in silence. On paper they look successful. Inside, they are running a second full-time job trying to appear “easy” and “low maintenance.” Burnout often arrives when they simply cannot perform at that level any longer.

Sensory overload and hostile environments

Sensory overload is another powerful driver of neurodivergent burnout. Many autistic and ADHD people experience environments differently: lights feel brighter, sounds feel louder, smells feel stronger, and multiple inputs can stack together quickly.

Open-plan offices, busy classrooms, crowded public spaces, and unpredictable schedules can keep the nervous system in a near-constant state of alert. Polyvagal theory, which looks at how the autonomic nervous system shifts between states of safety and threat, helps explain why this matters. When your brain decides an environment is unsafe, your body prepares for action instead of recovery, so rest is shallow and short-lived.

Over time, even settings that used to be tolerable may become too much. Someone who once managed a weekly grocery trip might now find the store unbearable, with bright lights, loud music, and bumping carts feeling like an attack rather than a minor annoyance. This shrinking tolerance is a common sign that burnout is building.

Why neurodivergent burnout is different from “regular” burnout

Many descriptions of burnout focus on long work hours, heavy workloads, and feeling emotionally distant from a job. These are real concerns, and they do affect neurodivergent people. However, neurodivergent burnout usually involves more than overwork.

Key differences include:

- Burnout can extend far beyond work or school. It affects self-care, hobbies, relationships, and daily living tasks, not just job performance.

- It is deeply tied to sensory and social mismatch. Even if hours are reasonable, environments and expectations may constantly clash with how your brain and body work.

- Masking and camouflaging play a central role. Many neurodivergent people burn out from trying to appear “fine” rather than from the tasks themselves.

- Loss of skills is common. People may temporarily lose abilities they relied on, such as driving to new places, organizing bills, or handling conversations, even though they still care about those things.

Understanding these differences can be a relief. If you recognize yourself here, it does not mean you are weak or incapable. It means your nervous system has been carrying more load than it can safely manage, and something in your demands, environment, or supports needs to change.

Signs And Symptoms Of Neurodivergent Burnout

Signs of neurodivergent burnout often show up in your emotions, your body, and your behavior long before you have language for what is happening.

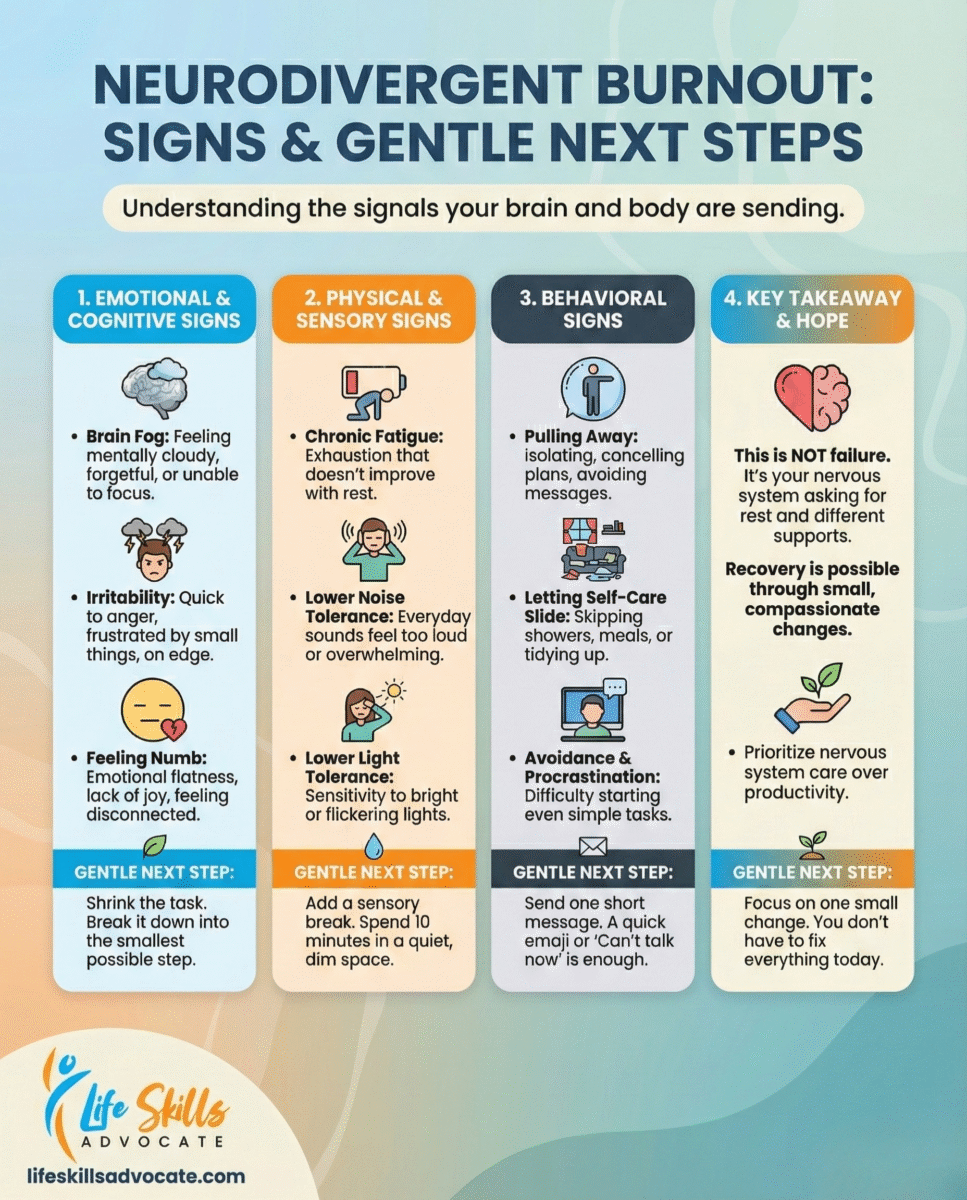

Emotional and cognitive signs

Emotionally, many people describe feeling flat, irritable, or on the edge all the time. Things that used to feel manageable now feel huge, and you may swing between feeling numb and feeling overwhelmed by small triggers. It can be harder to feel joy, interest, or connection, even with people and activities you usually care about.

Cognitively, burnout often brings brain fog. You might reread the same sentence over and over, stare at a task without starting, or lose track of what you were doing in the middle of a routine. Decisions that used to be simple, such as what to eat or which email to answer first, can suddenly feel impossible.

Descriptions in both research and community writing on neurodivergent burnout symptoms consistently mention this mix of emotional weariness and mental slowdown, especially after months or years of high stress and low support.

Physical and sensory signs

Burnout is not just “in your head.” It often shows up clearly in the body. Many people report chronic fatigue that does not improve with a weekend off, more frequent headaches or illnesses, muscle tension, stomach issues, and sleep changes. Your body may feel heavier, slower, or less coordinated than usual.

Sensory changes are especially common for neurodivergent people. Noises feel louder, lights feel brighter, and textures that were once tolerable can suddenly feel unbearable. You may start avoiding stores, public transport, group events, or even certain clothing because your nervous system cannot filter as much input as it used to.

If you want a deeper dive into the body side of burnout, our article on physical signs of burnout your body wants you to notice walks through common early warning signals in detail.

Behavioral signs and loss of skills

Behaviorally, neurodivergent burnout often looks like pulling away from life. You might cancel plans more often, stop answering messages, or log off social platforms because even low-effort contact feels draining. Self-care tasks such as showering, brushing your teeth, cooking, or tidying may start to fall away.

Autistic burnout research and autistic-led guidance describe a noticeable loss of skills during burnout, such as difficulty speaking, managing daily living tasks, or handling changes that were once routine. Guidance on autistic burnout highlights that people may feel “more autistic” than usual, with stronger sensory responses and less capacity for masking, after long periods of pushing through stress.

For many ADHD and otherwise neurodivergent people, this can look like missing deadlines, ignoring important mail, or abandoning routines that once helped. On the surface it may be labeled as procrastination or avoidance, but underneath it is often a nervous system that has reached its current limit.

How this can look in real life

If you relate to several of these signs, you are not alone. Neurodivergent adults often describe experiences like:

- Coming home from work and going straight to bed, then scrolling or staring at the wall instead of doing anything on your list.

- Feeling like every sound, light, or request from another person is “too much,” even if the day looked normal from the outside.

- Letting dishes, laundry, or emails pile up because starting feels impossible, then feeling ashamed or worried about what others will think.

- Finding that hobbies you once loved now feel like chores, so you stop doing them and feel even more disconnected.

These patterns are not proof that you do not care. They are signals that your brain and body are asking for relief from ongoing stress, mismatch, and masking.

| Common sign of neurodivergent burnout | What might be happening in your brain and body | Gentle next step you can try this week |

|---|---|---|

| Even basic self-care (showering, brushing teeth) feels impossible | Executive function and energy are depleted, so sequencing and starting tasks costs more effort than usual | Break the task into one tiny piece, such as sitting in the bathroom with the light dimmed or just washing your face, and count that as a win |

| Noises, lights, or textures that were fine before now feel unbearable | Your nervous system has less capacity to filter sensory input, so more signals are getting through as “urgent” | Use headphones, sunglasses, softer clothing, or shorter trips, and build in at least one short sensory break in a quieter space each day |

| You avoid messages, calls, or social plans, even with people you like | Social energy and decision-making are low, so your brain flags every interaction as extra work | Choose one low-pressure contact to respond to with a brief message like “My brain is tired, but I am thinking of you,” and pause there |

| Work or school tasks that used to be easy now take hours or do not get finished | Burnout is affecting attention, memory, and planning, so it takes more effort to stay on track | Shorten your to-do list to one to three key tasks per day, and talk with someone you trust about deadlines or accommodations where possible |

If you see yourself in several of these examples, it does not mean you have failed. It means your nervous system has been working hard for a long time and needs changes in pace, expectations, and support.

When To Seek Extra Support

Neurodivergent burnout is serious, and you do not have to manage it alone. Sometimes small changes and more rest are enough, and sometimes the safest and kindest step is to bring in more support.

It is a good idea to reach out for professional help if you notice any of the following:

- Safety concerns. You have thoughts about hurting yourself, feel like you cannot keep yourself safe, or notice a strong pull toward risky behaviors that are not typical for you.

- Ongoing loss of daily functioning. Basic tasks such as eating, hygiene, paying bills, caring for dependents, or attending work or school are slipping for weeks at a time.

- Very strong or persistent mood changes. Feelings of hopelessness, numbness, or anxiety are present most days and do not ease even when demands are lowered.

- Confusion about what you are experiencing. You are unsure whether what you are feeling is burnout, depression, anxiety, another health condition, or a mix, and you want help sorting it out.

In these situations, a healthcare or mental health professional, such as a primary care provider, psychologist, or therapist, can help rule out medical causes, assess for depression or anxiety, and work with you on a plan. When possible, look for providers who describe themselves as neurodiversity affirming or experienced with autistic and ADHD clients, since they are more likely to understand burnout in context.

Formal Tools Professionals Use To Measure Burnout

Some clinicians and researchers use standardized questionnaires to understand how severe burnout is and how it changes over time. These tools are not specific to neurodivergent people and are usually meant for use in professional or research settings, not as a do-it-yourself diagnosis. They can still be helpful to know about, especially if you are reading research or working with a provider who uses them.

- Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI): One of the most widely used burnout scales in workplaces. It focuses on three areas: emotional exhaustion, feeling distant or cynical about work, and reduced sense of effectiveness. Note: The MBI is a paid, licensed tool.

- Burnout Assessment Tool (BAT): A newer measure that looks at exhaustion, mental distance from work, and both cognitive and emotional problems linked to burnout. It is used in research and organizational settings. Note: The BAT is available for research and non-commercial use.

- Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI): A questionnaire that focuses on two main parts of burnout: exhaustion and disengagement from work or tasks. It has been used with a wider range of groups, not only helping professionals. Note: The OLBI is often available at no cost for academic and clinical use.

If you work with a clinician, they may use one of these tools or something similar alongside your own description of what life feels like. Your lived experience still matters more than any score on a form.

Skills-based supports can sit alongside clinical care. Executive function coaching, like our executive function coaching for adults and life skills coaching for neurodivergent minds, focuses on practical tools for planning, organization, and daily routines. Coaching is not therapy or medical treatment, it is one piece of a broader support system that can help you rebuild life around your real energy, needs, and values.

If you ever feel at immediate risk of harm, contact local emergency services or a crisis line in your area right away, then follow up with ongoing support once you are safe.

How Neurodivergent Burnout Affects Executive Function And Daily Life

Neurodivergent burnout does not only change how you feel, it also changes how your brain handles planning, memory, focus, and follow-through in everyday life.

Why burnout hits planning, memory, and focus

Executive functions are the skills your brain uses to organize, start, and complete tasks. They include planning, working memory, time management, and self-monitoring. When your stress systems have been active for a long time, these skills often become less reliable.

Research on burnout and cognitive performance shows that people experiencing burnout can have more trouble with attention, memory, and flexible thinking. In simple terms, the parts of the brain that help you plan and make decisions are working harder while also getting fewer resources, so tasks take more effort and mistakes are more likely.

For neurodivergent people, this combines with existing executive function differences. If you already work extra hard to manage time, keep track of details, or switch between tasks, burnout can feel like your usual supports have been taken away. Systems that once “just about worked” may suddenly stop working, even if nothing on your calendar has changed.

Everyday examples of executive function changes in burnout

When executive function is strained by burnout, day-to-day life often changes in very practical ways, such as:

- Staring at an assignment, email, or work task for an hour without starting, even when you know what to do.

- Missing appointments or deadlines because you forget to check your calendar or cannot bring yourself to open it.

- Walking into a room and forgetting why you went there many times a day, not just occasionally.

- Feeling unable to switch tasks, so you stay frozen on one thing or bounce between many tabs without finishing anything.

- Struggling to follow multi-step instructions that used to be simple, such as getting ready to leave the house or cooking a basic meal.

These shifts can be frightening, especially if you are used to being the organized one or the person who keeps everything running. Many people only notice how hard they have been working when those skills start to slip.

Why this is not proof that you are lazy or irresponsible

It is easy to tell yourself a harsh story when executive function drops. You might think “I am just lazy,” “I am falling apart,” or “Everyone else can handle this.” Those thoughts are common, especially for people who have spent years masking struggles or being judged for them.

From a stress and brain perspective, though, a different picture emerges. Chronic stress and high allostatic load pull energy away from long-term planning and fine-tuned control and into short-term survival. Your nervous system is trying to protect you, not sabotage you, even if the result is missed tasks or messy rooms.

Seeing your executive function changes as part of neurodivergent burnout can open up more helpful questions, such as “What can I remove or simplify right now?” and “Where can I ask for more structure or support?” instead of “Why can I not just get it together?” That shift in frame is often the first step toward recovery.

Recovery And Prevention: Practical Supports For Different Roles

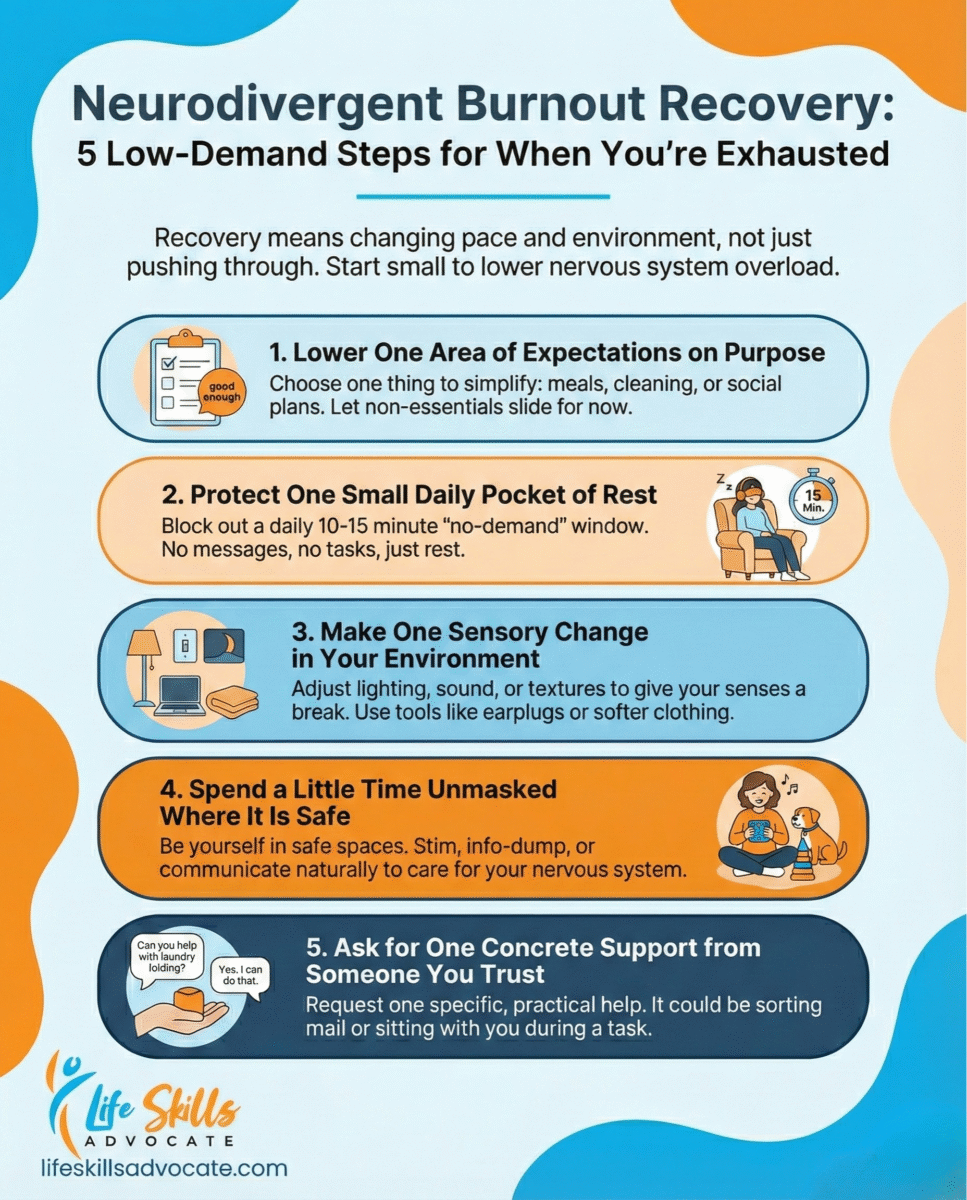

Recovering from neurodivergent burnout usually means changing both your pace and your environment, not just “pushing through” or taking one short break. Small, steady shifts can lower the load on your nervous system and reduce the chance of sliding back into the same burnout cycle.

For neurodivergent individuals: low-demand steps to start with

When you are already burned out, even helpful ideas can feel like more homework. It is usually better to start with very small, low-demand steps instead of trying to rebuild your entire life at once.

- Lower the bar on purpose. Choose one area of life to simplify for now, such as meals, housework, or social plans. That might mean more simple meals, fewer events, or a smaller to-do list.

- Protect one small pocket of rest. Block off a short daily “no demand” window, even if it is only 10–15 minutes, where you do not answer messages or tackle tasks.

- Map your energy gently. Notice which activities drain you the fastest and which ones give even a little bit of relief. You can jot this down in a note on your phone so it does not become a big project.

- Make your environment softer. Adjust lighting, sound, and seating so your senses get a break. Earplugs or headphones, softer clothing, closing one tab at a time, or using a smaller workspace can all help.

- Spend some time unmasked where it is safe. If you have people or spaces where you can stim, info-dump, or speak in your natural style, treat that as nervous system care, not a luxury.

If phone scrolling keeps your brain “keyed up” during breaks, a gentle friction tool can help. The tool Brick lets you pause certain apps while keeping essentials like messages or maps. This can make breaks more intentional without locking down your whole phone.

For work and school: accommodations that reduce burnout risk

Many neurodivergent people reach burnout because their work or school environment expects constant output without enough flexibility. Reasonable adjustments can make a real difference, even if you cannot change everything at once.

Ideas to consider include:

- More control over your schedule. Flexible start and end times, protected focus blocks, or fewer back-to-back meetings and classes.

- Clear, written instructions. Summaries of tasks, deadlines, and priorities in writing so you do not have to hold everything in working memory.

- Less sensory overload. Options for quieter spaces, noise-cancelling headphones, camera-off participation when possible, or seating away from high-traffic areas.

- Adjusted workload or deadlines. Spreading big tasks over more days, or shifting certain duties that are especially draining to others when possible.

Our article on work accommodations for neurodivergent employees explores these ideas in more depth.

For example, in a 2024 online survey of 2,000 neurodivergent Americans aged 20 to 43 conducted by the education platform EduBirdie, 91% said they masked their traits at work and one in three worried they could be fired if they disclosed their condition. The survey report on neurodiversity in the workplace shows how common masking and job-security fears are for neurodivergent workers, and experts note that this constant effort to “fit in” can contribute to burnout. Accommodations are not favors, they are tools that help people do their jobs more sustainably.

If you are in school, similar ideas apply. Disability services, IEPs, or 504 plans can sometimes provide extra time on tests, reduced-distraction testing rooms, or alternative formats for assignments. When formal supports are not available, even small informal agreements with teachers or professors, like clear deadlines or fewer group presentations, can help.

For families and caregivers: support without added pressure

Family support can make burnout easier to navigate, but only if it reduces pressure instead of adding more. Many neurodivergent adults and teens say that feeling believed and backed up at home makes the biggest difference.

- Believe what they tell you about their energy. If they say they are beyond their limit, assume that is accurate, even if the day “does not look that hard” from the outside.

- Reduce non-essential demands for a while. This might mean relaxing expectations about chores, social events, or grades while you all focus on stability and safety.

- Help with executive function where invited. Offer practical help like sorting mail, breaking down a task list, or sitting nearby while they tackle one small step.

- Protect recovery time. Guard quiet time and predictable routines, especially after school or work, so their nervous system has a chance to settle.

If you are a parent or caregiver and you feel drained yourself, resources on autism parent burnout can help you name your own limits and find ways to share the load.

For educators and clinicians: ND-affirming responses to burnout

Educators and clinicians are often the first people outside the family to notice burnout. How you respond can either reduce shame or increase it.

- Take functional changes seriously. If a student or client suddenly loses skills, withdraws, or shows stronger sensory responses, consider burnout as a possibility instead of assuming noncompliance.

- Ask about demands and supports, not just symptoms. Questions like “What has been taking the most energy lately?” or “Where do you feel most and least supported?” open more useful conversations.

- Adjust expectations when possible. This might include fewer concurrent projects, alternative formats for participation, or built-in recovery time after intense tasks.

- Use ND-affirming language. Frame burnout as an understandable response to chronic mismatch, not as a personal failure.

For deeper context on executive function and teaching, you might find our Executive Functioning 101 Resource Hub and posts on teaching executive function skills helpful when planning supports.

Tools and supports that can help

Many people recover from neurodivergent burnout by combining self-directed changes with structured support.

- Executive function coaching. Coaching focuses on building practical systems for planning, organization, and follow-through. Our executive function coaching for adults and life skills coaching for neurodivergent minds are skills-based services, not therapy or medical care, and can sit alongside clinical support when needed.

- EF-friendly environments and routines. If you want ideas for reworking spaces and tasks, our guide on how to make stuff more executive function-friendly offers practical examples that can be adapted during burnout recovery.

- Free assessment tools. Our free executive functioning assessment can help you or your learner identify which executive function areas feel most strained right now, which can guide what to simplify and where to seek help.

You do not have to use every tool available. Choosing even one supportive change in your environment, one conversation about accommodations, or one structured support like coaching can start to make burnout feel a little less permanent.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does neurodivergent burnout usually last?

There is no single timeline, but many autistic and ADHD adults say neurodivergent burnout lasts months or even years, especially if demands stay high and supports do not change. Research on autistic burnout research describes it as a long-lasting state, not a quick dip in energy. Recovery tends to be gradual and uneven, with good days and hard days, rather than a neat straight line.

How is neurodivergent burnout different from regular burnout?

Regular burnout descriptions often focus on work overload and feeling distant from a job. Neurodivergent burnout usually includes those pieces plus stronger sensory overload, more masking, and a drop in everyday skills such as self-care or managing routines. It tends to affect many areas of life at once, not only work or school, and is closely tied to a long-term mismatch between needs and environment.

How can I tell if I am burned out or just having a rough week?

A rough week usually passes when demands ease and you get a bit more rest. Burnout often sticks around even when you sleep more or take a short break. Signs like ongoing fatigue, brain fog, shrinking tolerance for noise or social contact, and a lasting drop in daily functioning over several weeks or longer point more toward neurodivergent burnout than a temporary spike in stress.

What is the difference between neurodivergent burnout and depression or anxiety?

There can be overlap. Depression and anxiety are mental health conditions that may include low mood, loss of interest, and physical changes such as sleep or appetite shifts. Neurodivergent burnout is a response to chronic overload, masking, and mismatch between demands and supports. Some people experience both at the same time. Because they can look similar from the outside, it is important to talk with a healthcare or mental health professional if you are unsure, especially if safety is a concern.

Can teens and college students experience neurodivergent burnout?

Yes. Teens and college students who are autistic, ADHD, or otherwise neurodivergent can experience burnout, particularly when they handle heavy academic loads, constant social expectations, and new independence with limited support. Signs might include grades dropping, missing classes, hiding in their room, or losing interest in activities they used to enjoy. In these situations, it helps to look at workload, sensory load, masking, and executive function demands, not only motivation.

What if I cannot reduce my workload right now?

If you cannot change the big picture yet, focus on smaller changes within it. That might mean shrinking your daily to-do list, blocking off short recovery windows, making your environment more sensory-friendly, or asking for one or two concrete accommodations at work or school. A skills-based support like executive function coaching for adults or using tools from our guide on making tasks more executive function-friendly can help you design systems that protect your limited energy while you plan longer-term changes.

Next Steps: Putting This Into Practice

When you suspect neurodivergent burnout, it can be tempting to create a huge recovery plan. In reality, small, repeatable actions are more realistic for a tired brain and body.

Here is a simple way to move forward without overwhelming yourself:

- Name what is happening. Start by gently saying, “I am likely dealing with neurodivergent burnout.” This shifts the story from “I am failing” to “I am overloaded,” which can make it easier to ask for help and set limits.

- Lower one area of demand. Choose a single category to simplify for the next few weeks, such as housework, social plans, or extra projects at work or school. Let a few non-essential things slide on purpose while you focus on stability and safety.

- Add one support. Pick one new support instead of many at once. That might be a small sensory change at home, one conversation about accommodations, completing the free executive functioning assessment, or scheduling a discovery call to learn more about executive function coaching for adults or life skills coaching for neurodivergent minds.

- Set a gentle check-in point. Choose a date a few weeks from now to notice what has changed. You might ask yourself, “Where do I feel even a tiny bit less overloaded?” and “What is still too much?” Use those answers to decide whether to lower more demands, add another support, or reach out for professional help.

You do not need to earn rest, and you do not have to fix everything at once. Choosing even one small step from this list is a valid way to respond to burnout and can be the start of building a life that fits your nervous system more kindly.

Further Reading

- Physical signs of burnout your body wants you to notice – Life Skills Advocate’s guide to early body-based warning signs that stress and burnout may be building before a full crash.

- Effective strategies for managing autism parent burnout – Support for parents and caregivers who feel drained while advocating for and supporting autistic children and teens.

- 20 essential work accommodations for neurodivergent employees – Practical examples of workplace adjustments that can reduce overload and burnout risk for autistic and ADHD workers.

- How to make stuff more executive function-friendly – Ideas for redesigning tasks, systems, and environments so they place less demand on planning, memory, and organization.

- Executive Functioning 101 Resource Hub – Collection of Life Skills Advocate articles and tools that explain executive function skills and how to support them at home, school, and work.

- Free executive functioning assessment – Self-report tool to help you identify which executive function areas feel most strained right now.

- Executive function coaching for adults – Skills-focused coaching support for adults who want help rebuilding sustainable systems, routines, and follow-through.

- Life skills coaching for neurodivergent minds – One-to-one support for autistic, ADHD, and otherwise neurodivergent learners and adults who want practical strategies for daily life.

- World Health Organization: Burn-out as an occupational phenomenon – Official ICD-11 description of burnout as a work-related syndrome of exhaustion, mental distance, and reduced professional effectiveness.

- Raymaker et al. (2020): Defining autistic burnout – Qualitative study describing autistic burnout as long-term exhaustion, loss of skills, and reduced tolerance to stimulus based on autistic adults’ lived experience.

- National Autistic Society: Understanding autistic burnout – Practitioner-facing overview of autistic burnout, including common features, risk factors, and practice considerations.

- Medical News Today: What to know about neurodivergent burnout – Consumer-friendly summary of what neurodivergent burnout can look like, possible causes, and general support options.

- Koutsimani et al. (2021): Burnout and cognitive performance – Research article discussing links between burnout and changes in attention, memory, and executive functioning.

- Verywell Health: Neurodivergent workers and job security fears – Discussion of masking, job insecurity, and workplace stressors that can contribute to burnout for neurodivergent employees.

- Brick phone break tool – App that adds gentle friction to certain phone apps, helping create more intentional breaks while keeping essentials available.