Autistic inertia is when starting, stopping, or switching tasks feels hard, even when you want to do the thing.

If you have ever searched “autism stuck” or “trouble switching tasks autism,” this might be the missing label. It can look like lying on the couch hungry, needing a shower, and still not moving. It can also look like being deep in something and feeling like you cannot stop without getting thrown off balance. This matters because autistic inertia can quietly affect basics like food, sleep, hygiene, schoolwork, and work reliability, plus it can create a lot of misunderstanding in relationships.

Also, I get the “my brain says nope” reaction too. If a plan has 14 steps, my odds of starting drop fast. So we are going to keep this practical and small-step on purpose.

TL;DR

Autistic inertia is real, common in autistic communities, and it is not a character flaw. A helpful first move is often to aim for a smaller state change, not “more motivation.”

- Autistic inertia often shows up as difficulty starting, stopping, or switching tasks.

- It can look like “stuck at rest” (cannot start) or “stuck in motion” (cannot stop).

- Many autistic people find that deep focus (sometimes described as monotropism), set shifting demands (cognitive flexibility), and stress or fatigue can make switching tasks feel harder.

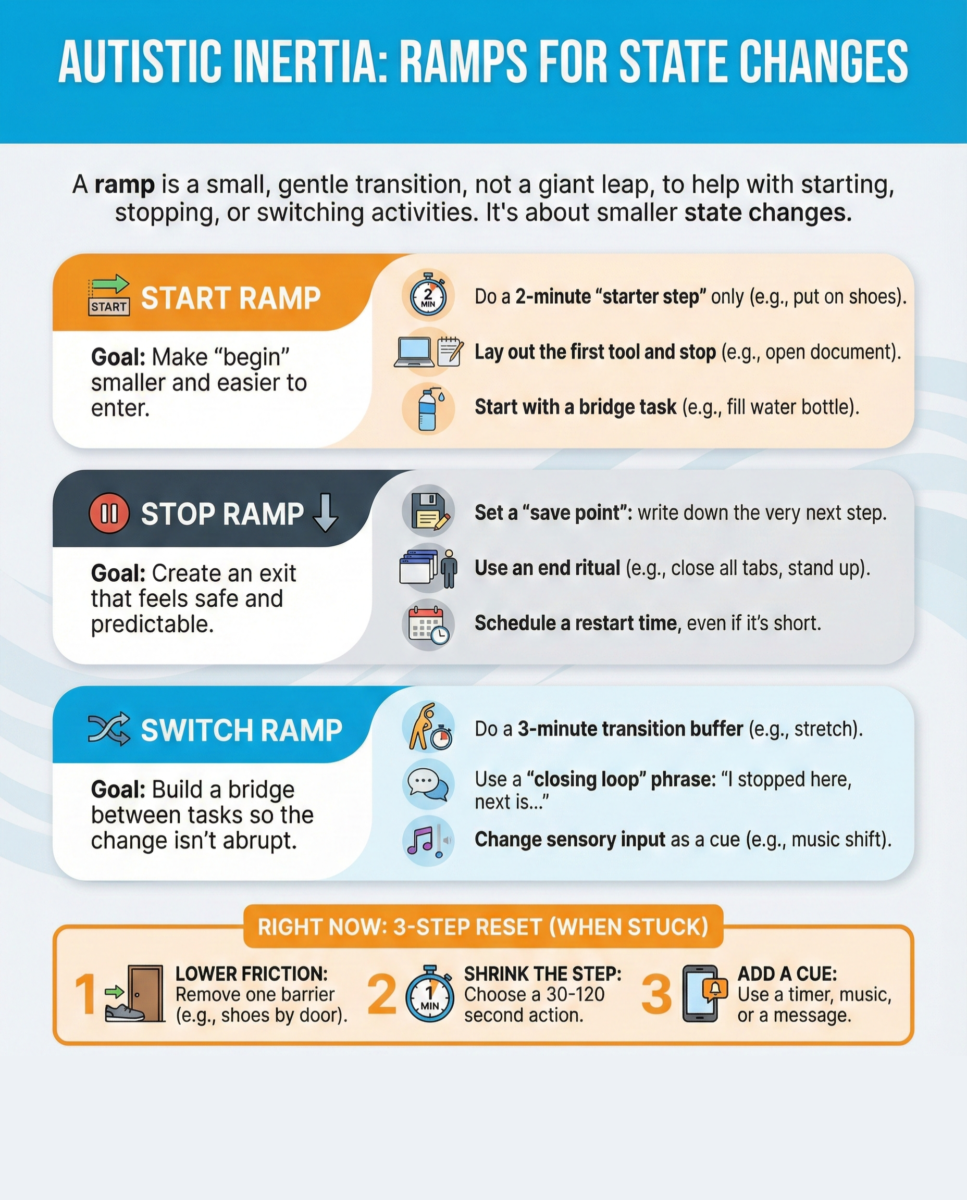

- Use ramps: Start ramps (tiny first step), Stop ramps (planned exit), Switch ramps (bridge between tasks).

- If tools are not enough, add an “outside force” option (body doubling, check-ins, environmental cues).

- Supporters can help most by lowering friction, reducing surprise, and collaborating on transitions.

Note: This post is educational and not medical, mental health, or legal advice. If inertia is affecting safety, basic needs, or mental health, it can help to talk with a qualified professional for individualized support.

What Is Autistic Inertia?

Autistic inertia is a lived-experience term used in autistic communities (and studied in qualitative research) to describe difficulty acting on intentions, especially when you need to start, stop, or switch activities.

Importantly, autistic inertia is not just “I do not want to.” It is often “I want to, and I still cannot get my body and brain to shift states.” In research with autistic adults, people describe difficulty starting, stopping, and changing activities that does not feel fully under conscious control, and many describe needing some kind of “outside force” to change gears.

Start inertia: when getting going is the hard part

Start inertia is the “stuck at rest” version. You might be thinking about doing the task, even worrying about it, and still not beginning. This is often what people mean by “task initiation” challenges.

Stop inertia: when disengaging is the hard part

Stop inertia is the “stuck in motion” version. You might want to stop, but your brain and body resist the break. Sometimes it feels like stopping will cost more energy than continuing.

Switch inertia: when transitions feel jarring

Switch inertia is when changing from one task, topic, or environment to another feels like a gear grind. This shows up a lot in “trouble switching tasks autism” searches, because the transition is the hard part, not the task itself.

What Does Autistic Inertia Feel Like Day-to-Day?

Autistic inertia often feels like a mismatch between intention and movement, like your “go” button is buffered.

Here is a composite example I have seen in coaching (details changed). An autistic adult gets home tired and sits down “for five minutes.” An hour later, they are still sitting, hungry, and annoyed with themselves. They can describe exactly what they want to do (eat, shower, send one email), but the next step feels weirdly far away, like it requires a running start.

That same person might also have the other side. Once they start a project, they can keep going for a long time. Stopping can feel risky because it might break focus, or because restarting later feels uncertain.

Why this matters: when you can name the pattern, you can stop arguing with yourself (or with other people) about motivation and start building supports that match the real problem: state changes.

Why Does Autistic Inertia Happen?

Autistic inertia usually is not one single cause. It is often a pile-up: attention gets sticky, switching costs are high, and stress or fatigue raises the cost even more.

Monotropism and “attention tunnels”

Many autistic people describe an attention style that is deep, focused, and interest-driven. The framework of monotropism is one way to describe that “attention tunnel” experience, including how hard it can be to shift attention once it locks on.

If your brain invests heavily in what is happening now, switching is not “just stop and do the other thing.” Switching can require time to disengage, reorient, and re-enter a new context. You can read a clear overview of this concept in the National Autistic Society’s explainer on monotropism.

Executive function and cognitive flexibility (set shifting)

Executive function is a group of skills that help you start tasks, plan, shift, inhibit, and monitor what you are doing. Research syntheses often find group-level differences in executive function measures in autism, with a lot of variation by person and by task.

One helpful subskill to name here is cognitive flexibility (also called set shifting). Set shifting is the ability to switch rules, switch tasks, or shift strategies when something changes. A meta-analysis found autistic participants, on average, showed differences in cognitive flexibility measures, while also emphasizing that results vary a lot across studies and individuals. If you want a research summary, see this meta-analysis on cognitive flexibility in autism.

Why this matters: if the bottleneck is task initiation or set shifting, a “try harder” message usually increases stress. A better fit is changing the environment and the first step so the brain can transition with less friction.

Stress, burnout, shutdown, and energy limits

Stress changes everything. When your nervous system is overloaded, even small tasks can feel huge. Autistic youth interviews about burnout, inertia, meltdown, and shutdown describe inertia as a “stuck” state with emotional, cognitive, and physical components, often misunderstood by adults. For a deeper look, see What I Wish You Knew (BIMS) From Autistic Youth.

If inertia has suddenly worsened, it can be useful to ask: “Is my brain protecting me from overload right now?” That question is often more helpful than “What is wrong with me?”

Autistic Inertia vs Procrastination vs ADHD Task Paralysis vs Burnout

These experiences can overlap, but they are not identical, and the most helpful supports can differ.

How autistic inertia differs from procrastination

Procrastination often involves delaying a task because it feels unpleasant, unclear, or anxiety-provoking. Autistic inertia can include those feelings, but the defining feature is often the state-change problem: you want to start (or stop), and the shift still does not happen.

Helpful reframe: instead of “I am avoiding,” try “I am stuck in a state.” Then choose a ramp (you will get a menu in the next section).

Autistic inertia vs ADHD task paralysis (and AuDHD overlap)

ADHD “task paralysis” is often described as wanting to do something but not being able to start, especially when there are too many choices, unclear priorities, or emotional pressure. Many AuDHD people experience both ADHD paralysis and autistic inertia, sometimes at the same time.

If you want a plain-language comparison and practical tools, you might like Life Skills Advocate’s guide on what task paralysis is and how to work with it.

When it might be burnout, shutdown, depression, or anxiety

Autistic inertia can be a steady trait-like pattern, but it can also spike during burnout, shutdown, high anxiety, depression, sleep deprivation, or major life stress. If you are noticing a sharp change, it may help to explore burnout supports alongside inertia supports.

For a practical overview of burnout patterns and recovery-friendly steps, see neurodivergent burnout signs and recovery.

Short, careful note on demand avoidance and “PDA profile” language

Some autistic people relate to “demand avoidance” or “PDA profile” language, especially if demands trigger a strong threat response. Not everyone finds this framework helpful, and it is discussed differently across regions and systems. If demands reliably create panic, shutdown, or intense resistance, the strategy layer often needs more emphasis on autonomy, collaboration, and reducing the felt sense of threat (not more pressure).

What Helps With Autistic Inertia? Use Start, Stop, Switch Ramps

If autistic inertia is a state-change problem, the goal is not “be more motivated.” The goal is to build a smaller, gentler transition from one state to another.

Think “ramps,” not “cliffs.” A cliff is “Go from couch to full shower routine now.” A ramp is “Stand up and walk to the bathroom. That is the whole plan for the next 60 seconds.”

A “right now” 3-step reset (when you are stuck):

- Lower friction: remove one barrier (shoes by the door, laptop open, towel ready).

- Shrink the step: choose a 30–120 second action that points in the right direction.

- Add a cue: timer, music shift, or a message to someone for a check-in.

Start ramps: make “begin” smaller

The most helpful start ramps usually do two things: reduce decisions and reduce the size of the first action.

- Use a “starter step”: pick the first tiny action and stop there on purpose. Example: “Put toothpaste on the toothbrush.”

- Set up the scene: put the tools in your path so the next step is obvious (clothes laid out, document already open).

- Borrow momentum: pair the start with something already happening (kettle on, microwave running, playlist starting).

If starting is a constant struggle across many tasks, it can help to read a broader overview of executive dysfunction signs and strategies, because autistic inertia often overlaps with executive function demands like task initiation and planning.

Stop ramps: create a safe exit

Stopping can be hard when your brain is finally locked in. A stop ramp protects the “future you” from having to re-find the thread.

- Create a save point: write a one-line note: “I stopped here. Next is ____.”

- Use a countdown plus ritual: “Three minutes to wrap up, then close tabs, stand up, water.”

- Schedule a restart: even a short planned return can make stopping feel less risky.

Switch ramps: build a bridge between tasks

Switch ramps are about respecting transition time. For many autistic people, switching is not instantaneous, so planning for it reduces friction.

- Transition buffer: build in 2–10 minutes between tasks (especially between social and solo tasks).

- Bridge task: choose a small action that links old task to new task (file the document, write the next step, then open the new tab).

- Reduce context switching when possible: batch similar tasks so you switch less often.

If your day requires lots of context switching, you may find Life Skills Advocate’s guide to task switching and context switching useful, even if you are not ADHD-identified, because the practical supports overlap.

When tools do not work: add an “outside force” option

In research and lived experience accounts, many people describe autistic inertia as something that does not reliably respond to internal pep talks. That is where “outside force” supports can help.

- Body doubling: do the start while someone else is present (in person or on video), even if they are doing their own task.

- Check-in prompts: ask a trusted person to text: “Want a 2-minute start together?”

- Environment cues: put the next step in your physical path (meds next to water bottle, shoes by door).

- Compatible activity: some people start more easily when there is a low-demand background activity (music, familiar show) that keeps the nervous system steadier.

Key takeaways

- Autistic inertia often improves when you focus on state changes, not motivation.

- A ramp is a tiny first step that reduces decision load and friction.

- Stopping is easier when you protect the restart with a save point.

- Switching is easier when you plan a buffer and a bridge task.

- If you are stuck, an “outside force” option can be a legitimate support, not a failure.

How Can I Support Someone With Autistic Inertia Without Power Struggles?

Support works best when it reduces friction and protects dignity, not when it adds pressure.

Why this matters: power struggles and repeated prompting often increase stress, which can make inertia stronger. Collaboration usually works better than escalation.

- Ask permission before prompting: “Do you want a reminder, or do you want quiet right now?”

- Offer two ramp options: “Do you want a 2-minute start together, or a 10-minute pause and then I check back?”

- Make the first step tiny and concrete: “Let’s stand up and walk to the kitchen. That is it.”

- Reduce surprise transitions: preview changes when possible (time warnings, written schedule, visual cue).

- Co-regulate: a calm presence, steady voice, and low language load often helps more than a lecture.

Scripts you can borrow:

- “What is the smallest next step your brain can tolerate?”

- “Do you want help starting, help switching, or help stopping?”

- “If we make this 10% easier, what would change?”

- “Want me to sit with you while you do the first two minutes?”

What Accommodations Help Autistic Inertia at Work, College, or School?

Accommodations help when they reduce transition load, reduce context switching, and make starts predictable.

Many supports that help autistic inertia are simple environmental or process adjustments. The goal is not to remove all demands. The goal is to make state changes manageable.

Workplace supports

- Meeting buffers: protect 5–15 minutes before and after meetings for switching.

- Written priorities: reduce “what do I do next?” decisions.

- Fewer simultaneous channels: limit rapid switching between chat, email, and meetings when possible.

- Clear “save points”: end-of-day notes that make restarting easier.

College supports

- Flexible participation options: written contributions when verbal switching is hard.

- Assignment scaffolding: checkpoints that support task initiation.

- Predictable scheduling: consistent routines and advance notice for changes.

Example message you can copy and paste (student to professor):

Hi Professor [Name], I wanted to share that transitions and task initiation can be challenging for me. Could you clarify the first step you recommend for this assignment (for example, outline vs draft)? If possible, I would also benefit from a brief transition buffer after class before jumping into group work. Thank you for your help.

School supports (IEP/504)

- Transition warnings: visual countdowns, “two more minutes,” or a written schedule.

- Start supports: teacher provides the first step, not just the final instruction.

- Reduced context switching: batch similar tasks, fewer abrupt rotations when possible.

- Alternate demonstrating of learning: reduce unnecessary switching between formats.

For more adult-focused transition ideas (work, life admin, routines), you can also explore transition strategies for autistic adults. For broader transition guidance, the National Autistic Society has a helpful overview on transitions and coping with change.

When Should Someone Get More Support for Autistic Inertia?

It is time to get more support when inertia is consistently blocking basic needs, school or work functioning, or mental health.

Consider extra support if you notice any of these:

- Regularly missing meals, sleep, hygiene, medication, or other basics because you cannot start.

- Frequent shutdown, panic, or distress around transitions.

- A sudden increase in “stuckness” that lasts weeks, especially with burnout signs.

- Safety concerns. If there is immediate risk, reach out to local emergency or crisis resources.

Sometimes the most helpful next step is a collaborative plan with a clinician, occupational therapist, or a coach who understands autistic executive function needs. Support should be practical and respectful, not shame-based.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is autistic inertia, in plain language?

Autistic inertia is difficulty starting, stopping, or switching tasks, even when a person wants to act. Autistic inertia can look like being “stuck at rest” (unable to begin) or “stuck in motion” (unable to disengage once started). Autistic inertia is a lived-experience term in autistic communities and it is also described in qualitative research with autistic adults. A helpful way to respond is to focus on small state changes (ramps) instead of trying to force motivation.

Is autistic inertia the same as executive dysfunction?

Autistic inertia overlaps with executive function demands, but autistic inertia and executive dysfunction are not the same thing. Executive function is a set of skills like task initiation, planning, inhibition, working memory, and set shifting. Autistic inertia describes the felt experience of getting stuck in a state, especially around starting and switching. Many people experience both, which is why strategies like reducing decision load, shrinking the first step, and creating transition buffers can help.

How is autistic inertia different from ADHD task paralysis?

Autistic inertia and ADHD task paralysis can look similar because both can involve wanting to start a task and feeling unable to begin. Autistic inertia often centers on state transitions (start, stop, switch) and the “switch cost” of changing gears. ADHD paralysis often involves difficulty with prioritizing, choosing, or initiating when the task feels unclear or emotionally loaded. Many AuDHD people experience both, so a practical approach is to use ramps plus ADHD-friendly supports like clear priorities and external structure.

Why do timers and reminders sometimes not work?

Timers and reminders often fail when the barrier is not forgetting, but switching states. A timer can signal “switch now,” but it does not automatically provide transition time, reduce sensory load, or create a safe exit from focus. When timers do not help, try pairing them with a switch ramp: a 3-minute buffer, a “save point” note, and a bridge task. For some people, an outside-force support (body doubling or a check-in) works better than a solo reminder.

How can I help my autistic child (or partner) transition without a meltdown?

The most helpful support is usually reducing surprise and collaborating on the transition plan. Start with consent: ask if prompting helps or hurts in that moment. Offer two ramp options (for example, “2-minute start together” or “10-minute pause and then check-in”). Use short, concrete language and keep the first step tiny. If distress is rising, lowering demands and increasing co-regulation (calm presence, fewer words, predictable cues) is often more helpful than escalating pressure.

Can autistic inertia get worse with burnout or stress?

Yes, autistic inertia can worsen when stress, fatigue, sleep debt, or burnout load is high. When the nervous system is overloaded, the brain may struggle more with initiation and shifting, and the body may feel “stuck” more often. If inertia has intensified recently, it can help to address burnout basics (rest, reducing non-urgent demands, predictable routines) alongside ramps. If functioning drops sharply or mental health concerns increase, individualized professional support can be important.

What accommodations help autistic inertia at work or in college?

Accommodations help most when they reduce transition load and context switching. Examples include transition buffers between meetings or classes, written priorities, clear first steps for assignments, predictable schedules, and fewer rapid-fire communication channels. A “save point” practice (writing the next step at the end of a work block) also makes restarting easier. In college, disability services can support adjustments that help with task initiation and transitions, especially when there is a clear functional impact.

Next Steps: Putting This Into Practice

The goal for next week is not a new personality. The goal is one better ramp.

- Pick one friction point: showering, meals, bedtime, starting work, ending work, switching tasks.

- Choose one ramp: start ramp, stop ramp, or switch ramp.

- Run a 7-day experiment: keep it small enough that you will actually try it.

- Add support if needed: body doubling, check-ins, or environmental cues are legitimate supports.

If you want a clearer picture of which executive function skills are getting taxed most, you can use the free executive functioning assessment as a starting point. If you want help building ramps that fit your real life, Life Skills Advocate also offers executive function coaching (coaching, not therapy).

About this post

Written by: Chris Hanson, founder of Life Skills Advocate (neurodivergent former special education teacher and executive function coach).

Last updated: January 24, 2026

How this was sourced: Peer-reviewed qualitative studies, meta-analyses, and guidance from major autism organizations, plus limited social listening for real-world phrasing.

Scope and limits: Educational only, not medical or mental health advice. For individualized support, consult qualified professionals. Coaching is an educational support service, not healthcare.

Further Reading

- First-hand accounts of autistic inertia (qualitative study)

- Autistic inertia themes from online community discourse (qualitative analysis)

- Autistic youth insights on burnout, inertia, meltdown, and shutdown

- Meta-analysis of executive function findings in autism

- Meta-analysis of cognitive flexibility (set shifting) in autism

- Monotropism overview (National Autistic Society)

- Transitions guidance (National Autistic Society)

- Executive dysfunction signs and strategies

- Task paralysis: what it is and how to work with it

- Task switching and context switching supports

- Autism transition strategies for adults

- Neurodivergent burnout signs and recovery

- Free executive functioning assessment

- Executive function coaching